By Thea Tjepkema

Dramatic soprano Helen Walker King (1898-1957) was an important Black voice in Cincinnati during the first half of the 20th century as a highly regarded singer, public school teacher, and leader advocating for vocal and choral music. Lovingly referred to as “Cincinnati’s soloist,” she was featured in numerous concerts, recitals, and events in churches, clubs, and major venues such as the Emery Auditorium and Music Hall. She was also heard on Cincinnati radio stations WLW and WKRC.

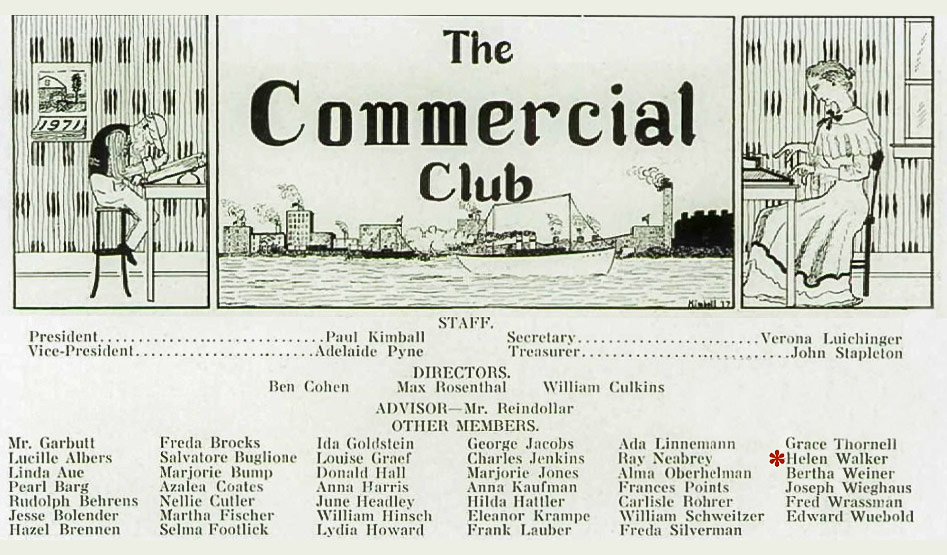

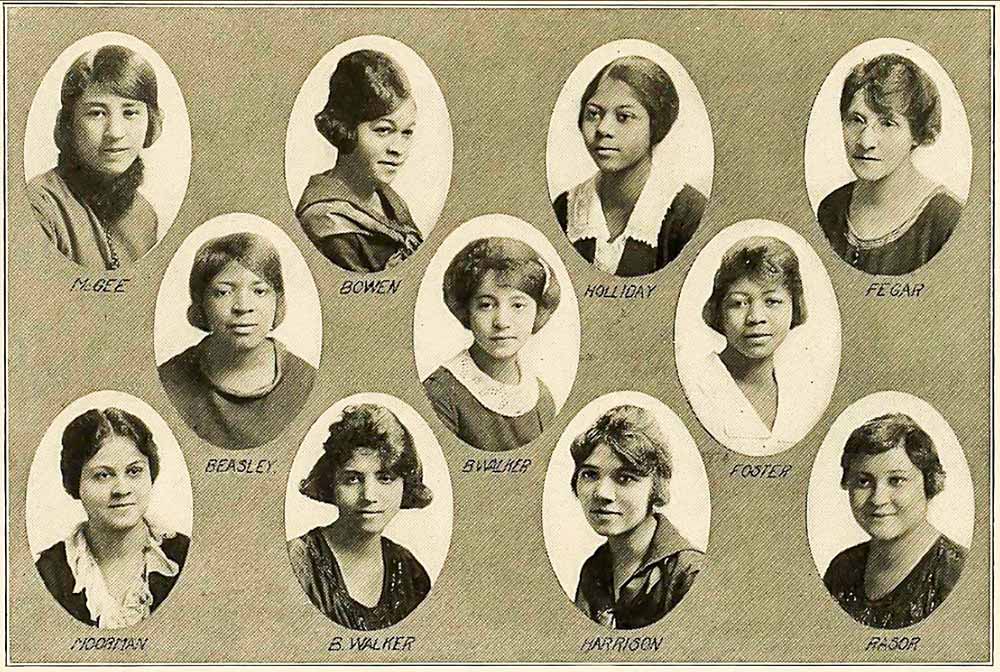

The Annual, 1917, p. 67.

Most notably, King was a founder of the “Negro Folk Song Festival” in 1932, including an African American choir of more than 200 members who performed in Eden Park. The festival, which hosted annual concerts, was the progenitor of the legendary June Festival, held annually between 1938 and 1952. Helen, her sister Breta, their parents Rev. J. Franklin and Hattie Walker, and Helen’s husband Rev. Charles N. King were among the most influential Black Cincinnatians of their time. Their contributions to the quality of life in Cincinnati still resonate today.

EDUCATOR & VOCALIST

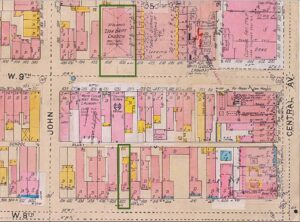

Zion Baptist Church, 430 W. Ninth. 1904 Sanborn Insurance Map V.1, #53.

Helen Cooper Walker grew up in Cincinnati’s West End (on W. Eighth St. and W. Ninth Ave.) loving music and singing in her father’s nearby Baptist church choir.

In the summer of 1924, Helen attended the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, studying voice with prestigious tenor Clarence B. Shirley, who also taught fellow Cincinnatian Nadine Roberts Waters.

2825 Alms Place and Chapel, Walnut Hills, razed in 1972.

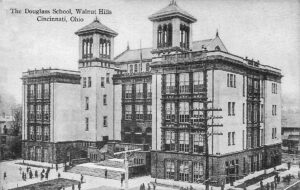

Helen was devoted to her life in education, teaching at Frederick Douglass Elementary public school for more than 25 years between 1922 and 1955.

She was the first female and youngest trustee of Wilberforce University from 1926-1929. Appointed by the Governor of Ohio to represent Hamilton County, her board leadership of the Combined Normal (teacher training) and Industrial Department meant traveling to five meetings a year in Wilberforce, Ohio, during her three-year appointment.

At 21-years-old she moved with her parents and younger sister, Breta, from downtown into their home in Walnut Hills at 3240 Beresford Avenue (razed).

THE ACCOMPLISHED WALKER FAMILY

FATHER: REV. JUNIUS FRANKLIN WALKER (1873-1957)

Who’s Who Among the Colored Baptists, p.138.

At seven years old, Helen moved to Cincinnati with her parents and sister from Indianapolis, Indiana, having lived in several towns where her father was a successful preacher; including Trenton, New Jersey, where she was born on Christmas Day in 1898. In 1905, her father, Reverend J. (Junius) Franklin Walker, was appointed pastor at Zion Baptist Church downtown Cincinnati at 430 W. Ninth (razed). In 1914, he became pastor for 43 years of the Metropolitan Baptist Church until his death. Metropolitan Baptist’s congregation first met in a storeroom at 124 E. Fourth Street, loaned by J.G. Schmidlapp.

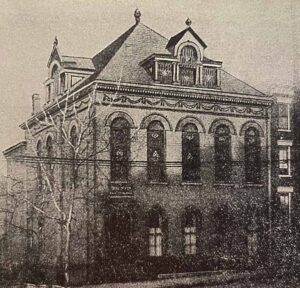

Rev. Walker was instrumental in organizing more than 300 members to purchase the Adath Israel Jewish Synagogue in the West End on the northeast corner of Ninth and Cutter streets (razed), which became the new home of Metropolitan Baptist Church on December 10, 1916 (thereafter listed as Metropolitan Baptist Temple in city directories).

Junius Franklin Walker’s parents died before he turned eight years old. He took night classes at the Y.M.C.A. high school in Richmond, Virginia and at the preparatory department of the Virginia Baptist Seminary in Lynchburg, while working as a cooper during the day. He studied teaching and theology at Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., and with a scholarship from the Pennsylvania Baptist Board of Education finished a three-year degree at Temple University in Philadelphia. He first preached at the Fifth Street Baptist Church in Richmond, Virginia, and was ordained at the Shiloh Baptist Church, Trenton, New Jersey, in 1898, where he served for eleven months. He successfully built the congregation and a new church in McDonald, Pennsylvania, before he accepted the pastorate of the First Baptist Church in Chillicothe, Ohio, in March 1901. In 1902, he received an honorary Doctor of Divinity from Guadalupe College in Seguin, Texas. From 1903 to 1905, Rev. J. Franklin Walker led the Corinthian Baptist Church, Indianapolis, Indiana, before moving to Cincinnati.

1904 Sanborn Insurance Map V.1, #52

Who’s Who Among the Colored Baptists of the United States declared Walker was brilliant at finances and real estate transactions, paying off the fifty-year mortgage of Zion Baptist Church and owning several valuable properties in Cincinnati. In August of 1918, Rev. J. Franklin Walker attended the National Negro Business League in Atlantic City, New Jersey and The New York Age described him as having an air of culture and refinement. This Black newspaper article about the business convention mentions his wife’s battle with indigestion and his patented cure – Walker’s Dyspepsia Compound.

1904 Sanborn Insurance Map V.1, #49

His product was made and sold at 1023 (W. Ninth) Cincinnati, Ohio, his home address, and in New York (wholesale or retail) at Dr. Eisenbud & Co., 478 Lenox Ave, Harlem. Walker’s business had sold over 6,000 bottles in 1918, the second year on the market. In real estate Rev. Walker owned $40,000 worth in property values.

The New York Age, Aug. 31, 1918, p.7.

Rev. Walker supported his church and was a trustee of the American Baptist Seminary in Nashville. He was vice-president of the National Baptist Convention. He also organized the first Ohio Baptist State Convention in 1919 as its first president and was elected president emeritus in 1954 by a membership of 300 churches. Metropolitan Baptist was an important gathering place for Cincinnati’s Black community, hosting several recitals, revivals, and political rallies with prominent soloists and speakers. According to The Cincinnati Post, Harry Clay Smith of Cleveland, a Black gubernatorial candidate that the Republican Party refused to place on the ballot, spoke there in 1922. At the National Association of Colored Women convention (N.A.C.W.) held in the Metropolitan Baptist Church in 1954, Maxwell M. Rabb, counsel to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, read Mrs. Mamie Eisenhower’s address praising the late N.A.C.W.’s first president Mary Church Terrell. In 1947, the highly respected Rev. J. Walker was presented $2,000 for his years of service from the Ohio board of the state convention to attend the World Baptist Alliance meeting in Copenhagen, Denmark.

MOTHER: HATTIE (HARRIET) R. BROWN (1877-1972)

Harriet Brown grew up in Philadelphia, where her father, Robert, was the first African American policeman and served 27 years. In 1898, Hattie R. Brown married Junius Franklin Walker in Philadelphia, where they may have met, both studying at Temple University. Mrs. Walker attended the University of Cincinnati as a "special student" states her biography in Dabney's Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens. She later took courses in School Library Administration at Columbia University in New York. Cincinnati directories list her as a milliner at their home. She was active in her husband’s church, where she played piano. She was a teacher at the Harriet Beecher Stowe School (635 W. Seventh St.) where founder Jennie Porter was the principal (1914-1936). In 1922, Hattie Walker became Cincinnati’s first Black public librarian at the main branch. Two years later, she transferred to the Harriet Beecher Stowe branch located in the school and worked there until retiring in 1948. She was active on the Y.M.C.A. management board and chair of its religious education committee for three terms and founded the regional Interdenominational Wives of Ministers Association.

In 1965, Hattie Walker was selected as “Woman of the Year” for the Beta Zeta Zeta Chapter of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority. She lived at their home in Walnut Hills until 1959 and then moved to Madisonville (5062 Anderson Place).

University of Cincinnati, The Cincinnatian, p.285.

HELEN’S SISTER: BRETA A. WALKER GRANNUM (1902-1991)

University of Cincinnati, The Cincinnatian, p.204.

Breta followed in Helen’s footsteps, attending Woodward High School, receiving a B.A. from the College of Arts and Sciences in 1924 and a Bachelor of Education in 1925 from U.C., then becoming a public-school teacher at Harriet Beecher Stowe and Frederick Douglass Elementary in Walnut Hills. In 1922 Helen was vice president of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority at U.C. and organized a play called “Everywoman,” which both she and Breta performed in at Hughes High School. Breta and Helen were founding members of the Sigma Omega Chapter of the Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA) Sorority, chartered by six Cincinnati women on December 18, 1924. Breta married Rev. Stanley E. Grannum (1891-1951), in 1931, a pastor in Cleveland, Ohio, and president of Samuel Huston College and Chair of the theology department at Gammon Theological Seminary in Austin, Texas. Breta’s obituary notes she died in her home in Madisonville and was musical like her sister – “known for her piano playing.” The Walker family is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery.

HELEN MARRIES REVEREND CHARLES NEWTON KING (1896-1975)

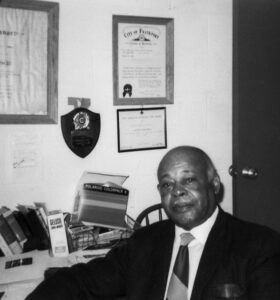

First Corinthian Baptist Church, Frankfort, KY,

Community Memories Project, Kentucky Historical Society.

In Cincinnati on November 16, 1927, Helen C. Walker married veteran Colonel Charles Newton King, whose occupation is listed as “chemist” on their marriage license. Reverend W.A. (Wilber Allen) Page of Union Baptist Church officiated. King graduated from Fisk University, magna cum laude in 1917, receiving a B.A. in science with a focus in agriculture, and delivered a commencement address. He registered for the draft while living in Chicago and served in WWI for ten months (June 1918-March 1919) before moving to Cincinnati in 1927. The city directory lists King as secretary for the Supreme Life Insurance Company during his first year in Cincinnati. He was a principal of South Woodlawn School before it became subsumed by the Lockland School District in 1938. His dismissal caused a strike by 390 African American students. He went on to earn a master’s degree in education from the University of Cincinnati Teachers’ College in 1940. King was the editor of the African American newspapers the Cincinnati Call & Post (1943-1945) and publisher and co-editor of the Cincinnati Voice (1944-1953). In 1942, King became the assistant pastor of his father-in-law’s Metropolitan Baptist Church for 13 years. When Helen became sick, he worked and then moved to Frankfort, Kentucky, to become the pastor of the First Corinthian Baptist Church from 1951 until his death in 1975.* He was the first African American to serve and hold office as second vice president of the Southern Baptist Convention and vice president of the Kentucky Baptist Convention.

THE HELEN & CHARLES N. WALKER HOME

Charles and Helen King lived their first two years of marriage in the Walker family home and in 1929 moved into their own home at 3042 Bathgate Street (razed), where they lived for 25 years. In 1950, The Union noted Mrs. Helen Walker King was “still in the hospital, but much better,” and she retired from teaching in 1955. Her obituary in 1957 reported she had finally succumbed to the illness she had for several years.

A POPULAR SOLOIST IN CHURCHES & MAJOR VENUES

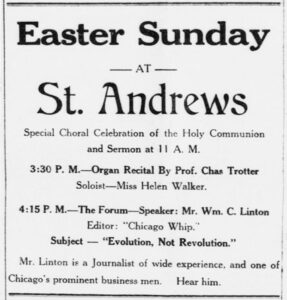

The Union, April 3, 1920, p. 3.

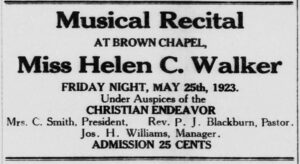

The Union, May 26, 1923, p.1.

Helen began her career singing in her father’s church as well as several African American churches across Cincinnati between 1915 and 1945, including Carmel Presbyterian, St. Andrews Episcopal, Union Baptist, Park Street M.E., and Allen Temple A.M.E. in downtown Cincinnati, and Brown Chapel and First Baptist Church in Walnut Hills. In 1923 she starred in a benefit concert for the United Negro Improvement Association at the Emery Auditorium. The Union review reported, “Her versatility and remarkable renditions elicited great applause.” She sang repertoire from classical to spirituals; and her sister Breta was given kudos for creating the elaborate costumes. The following year, Helen went on a concert tour with the “Redpath Chautauqua” group (a cultural festival movement) across Canada during its peak jubilee year. On March 17, 1929, Helen Walker “of the West End Branch Y.W.C.A.” sang “The Great Awakening” for the dedication ceremony of the Y.W.C.A.’s new building at Ninth and Walnut streets. The Cincinnati Times Star announced a recital on February 23, 1932, hosted by the Cincinnati Theological Seminary presenting Helen Walker King, dramatic soprano, at The Isaac M. Wise Center in Avondale (Reading Rd. & N. Crescent Ave. – today N. Fred Shuttlesworth Circle). On December 9, 1932, she was noted for her outstanding solo performance, along with tenor William Gee of the voice faculty of the Cosmopolitan School of Music, in the Cincinnati Civic Opera Company’s (Lillian Aldrich Thayer, Dir.) “In a Persian Garden” at the U.C. Wilson Memorial Auditorium. In 1933, after a lecture on Primitive Art at the Gibson Hotel, Helen sang Charles Wakefield Cadman’s “Thunder Water.”

Oct. 20, 1900, vol.33, issue 42, p.1559.

Several recital and concert advertisements mentioned Helen Walker King had also studied at the Chicago Musical College (records of classes she attended there have not been found) and with internationally recognized soprano Minnie Tracey, who settled in Cincinnati and became known for her private vocal lessons in her studios on East McMillan Street (184 and 1231) and in 1926 in her home at 1359 Fleming Street, still standing in Walnut Hills. Tracey collaborated with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra to create a production of Orpheus, a Mozart Festival, and regular live radio broadcasts.

KING IS A STAR IN CINCINNATI MUSIC HALL

On November 21, 1929, Helen Walker King was the featured soloist in Music Hall in one of the most spectacular events of her career: a Fall Festival Concert benefiting the Ninth Street Y.M.C.A. (a branch for African Americans established in 1913). The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune review mentioned it was an annual pageant and festival program of the “united negro choirs of Cincinnati.” The concert was divided into six parts, each devoted to types of choral music: orchestral, patriotic, solo vocal, choral, “Jubilee,” operetta, and a grand finale, with a mammoth chorus comprised from 26 organizations – mostly Black church choirs from Cincinnati, Covington and Newport, Kentucky, conducted by R. Alwyne Austin of New York – accompanied by musicians and the mighty Music Hall organ. The patriotic portion, included the audience joining in singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (listed as the “Negro National Anthem”) and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The Y.M.C.A. bugle corps and chorus performed “Choral Taps.” The “Recital” portion of solo vocal works featured King singing several classical arias including “Softly awakes my heart” from Saint-Saens’ Samson and Delilah, “Inflammatus et accensus” from Rossini’s Stabat Mater and Michael Costa’s “Zion, Awake.” This part finished with the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s Messiah, also a May Festival choral tradition. The “Jubilee” portion of the program included spirituals and gospel selections: “Got Good Religion,” “God’s Going to Set This World on Fire,” “Everybody Will Be Happy,” “Going Home,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and “Prayer from the Heart of Emancipation.” Other local soloists were Mrs. N. Dillehay, Mrs. A.M. Dunn, and Mrs. Alda A. Austin (wife of the conductor). The Max Yergen Quartet of the Ninth Street Y.M.C.A. and other instrumentalists included Mrs. Geneva Craig, Marie Thomas, Charles Trotter, and Helen Greer. For the grand finale pageant a gospel piece composed by R. Alwyne Austin, “World of Peace,” featured singers in national costumes forming a giant wheel with a single girl in the center, a quartet of men as the hub, women’s chorus as spokes, and men’s chorus as the wheel representing “the inevitable coming of peace among nations” through music.

HELEN WALKER KING: FOUNDER OF CINCINNATI’S AFRICAN AMERICAN CHORAL FESTIVAL

The Fall Festival Concert of 1929 in Music Hall was a rarity of its day. Black artists were seldom engaged in performances in Springer Auditorium, and audiences were routinely segregated by seat location and performance dates. The May Festival did not accept Black singers until 1956. The uplifting power of music was denied to too many people, and Helen Walker wanted to do something about it.

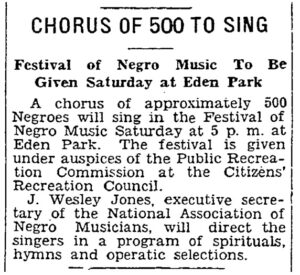

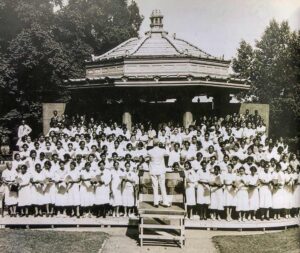

In August 1932 the Times Star mentioned Helen Walker King, soprano, sharing with A.N. (Alfred Nelson) Quarles, bass singer and choir director at Allen Temple, the active leadership of a large chorus of 250 that “will sing spirituals for the festival of Negro music in Eden Park.” Featured in the evening concert on Saturday, August 27, was the Cosmopolitan Four, a male quartet and Gladys Tatum, soprano, director of the choir of Brown Chapel. Tatum sang “On My Journey” and “Didn’t It Rain?”; the Cosmopolitan Four sang “Little Liza Jane” and “other songs of a similar nature from the wealth of Negro folk music.” In 1933 the Times Star announced a planning meeting in City Hall for the second annual “Festival of Negro Music.” The meeting was under the direction of Helen Walker King, chair of the music committee of the Citizens’ Recreation Council, an advisory group to the Public Recreation Commission. Many of Cincinnati’s most notable African Americans made up the committee, including Artie Matthews, William Gee, Helen Greer, and Loretta Manggrum. DeHart Hubbard, supervisor of African American activities and Harry Glore, supervisor of music for the Public Recreation Commission, were to assist the Music Committee. Glore’s address, starting the meeting, was titled, “The Value of Music in Promoting Inter-Racial Relations.” The Music Committee led by King gathered pledges from 500 singers in groups from across the city, organized rehearsals, and hired guest conductor, John Wesley Jones, music director of Chicago's Metropolitan Community Church and executive secretary of the National Association of Negro Musicians. The committee also organized a children’s chorus rehearsed by choral music teachers, Marie Thomas, of Douglass Junior High School and Helen Greer, of Stowe Junior High School. The second annual concert was held in Eden Park June 24, 1933, 5 p.m., and featured “folk songs of the race.” The 1934 program of “Negro Folk Songs” with 300 voices and six soloists, including Helen Walker King and William Gee, was held in Hughes High School on December 7, 8:30 p.m. Again, in Hughes High School, the Recreation Commission reported a concert of a mass African American chorus held in April 1935. On June 13, 1936, an episodic musical, "Why Not Try God," was held in Eden Park near the bandstand. St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, Social Services Department, hosted the event, declared the fourth annual Festival of Negro Religious Music by the Enquirer. Alfred Segal, a journalist for The Cincinnati Post, reported that 97-year-old Aunt Sarah Marshall would make her yearly trip (as she had the past three) to Eden Park to sing "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" in this year's big event. Mr. Albert E. Smith was the musical director of the 250-member choir of St. Andrew's and the vocal teacher of a young man, Saul, the lead soloist.

TALENTED MASS CHOIR PERFORMANCES LEADING UP TO THE 1938 “JUNE FESTIVAL”

The Cincinnati Post, June 23, 1933, p. 22.

Whether this large African American choral festival happened in 1937 cannot be determined, but on February 23, 1936, a Musicale at the Ninth Street Y.M.C.A. featured Helen Walker King singing Teresa Del Riego’s “Homing Song” and Waldemar Thrane’s “Norwegian Echo Song” accompanied by Clinton Gibbs. Also, on the program: baritone William Gee sang two pieces; a string ensemble performed Kreisler, Brahms, Mascagni; the Central Parkway Quartet played Strauss’ “Blue Danube Waltz”; and several violin and piano solos concluded with Debussy’s “Golliwog’s Cakewalk.” On January 1, 1938, a cast of 250 African Americans performed a pageant to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation in the Emery Auditorium with Helen Walker King as a soloist. In June of that year the newly formed “June Festival,” built upon the success of the previous “Negro Folk Song Festivals,” was held in the Eden Park bandstand with 4,000 listeners. The following year, Dr. Clarence Cameron White, a violinist, and graduate of Oberlin College, became the musical director, with a chorus of 300 and nationally renowned soloists.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati History Library.

For the next 14 years June Festivals would celebrate Black music making of the highest order and include artists such as Paul Robeson and Todd Duncan, while local talent always took center stage. June Festival ended in the 1950s, around the time the May Festival Chorus became integrated, but in Music Hall, the annual American Negro Spiritual Festival (1982-1998) and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra's Classical Roots concerts (est. 2001) continue the celebration of Black excellence Helen King began. The foresight, devotion, and dedication of Helen Walker King and her committee in building performance opportunities for Black Cincinnatians, created a renaissance that helped define the ethos of the region.

SINGING OVER THE AIRWAVES & RECORDINGS

Helen Walker King sang on WLW radio in February 1928 for a program of the Cincinnati Pan-Hellenic Association for Negro History Week with Cincinnati’s well-known African American pianist, Helen Greer, whom she worked with on many occasions. In April she was heard on WLW again singing John Rosamond Johnson’s “Li’l Gal” as a featured soloist for a program of local Black musicians performing works by famous Black composers, including her sister Breta in a double quartet singing “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” In 1955 an advertisement in the Cincinnati Post mentions recordings for sale at The Song Shop, 36 E. Fifth Street, of Helen Walker King with organ, singing the hymn “A Child of the King” and a spiritual “I Couldn’t Hear Nobody.”

1940–1945: A LAST PERFORMANCE IN CHICAGO WITH ARTIST THELMA JOHNSON STREAT

In the 1940s, Helen Walker King continued to sing solos at the Metropolitan Baptist Church and sang “familiar and less-known Negro spirituals” for the Wyoming Music Club tea themed “American Folk Music” held at Mrs. E.H. Eberle’s home (2845 May Street-razed) in Walnut Hills. She soloed at the second annual membership drive of the Black women’s Sojourner Truth Republican Club at the Nash Community Center (Altoona and Walters streets), and, at the Manse Hotel, sang for a tea of the Mt. Zion Methodist Church Woman’s Society of Christian Service.

Perhaps, the final performance of her career was in 1945, when she sang in Chicago at the unveiling of important new murals by Thelma Johnson Streat, depicting African Americans in industry at Kimball Hall (today the Lewis Center at DePaul University). A distinguished Black artist and dancer, Streat performed dance interpretations of her murals set to the vocal stylings of Helen King.

Helen Walker King used her voice as a singer and as an agent of change. During a time of segregation, her devotion to creating singing opportunities for all, by helping create the “Negro Folk Festival” and later the June Festival, brought together classically trained Black choruses and soloists for thousands upon thousands of Cincinnatians who were not welcome in Music Hall. A tireless advocate for the power of music to change lives, her life ended at the age of 58 on May 23, 1957, one year after the May Festival was opened to all, regardless of race.

Thea Tjepkema serves the Friends of Music Hall Board of Directors as a historic preservationist, historian, archivist, and curator. She has created two Speaker Series: Under One Roof: The African American Experience in Music Hall and Muses: The Women of Music Hall.

Contact us by email or call (513) 744-3293 to schedule a presentation for your group or organization.

THANK YOU to the archivists and librarians of the University of Cincinnati Libraries; Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library; Wilberforce University-Rembert E. Stokes Library, OH; Roosevelt University, Chicago; Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort; New England Conservatory of Music Archives, Boston; Fisk University-John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library, Nashville; Virginia Union University-L. Douglas Wilder Library; Wise Temple Library and Archives and The Jacob Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH.

THANK YOU, Rick Pender, Friends of Music Hall Board, for your editing expertise.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Helen Cooper Walker King (b. Trenton, NJ, Dec. 25, 1898-May 23, 1957, d. Cinti, Spring Grove Cemetery)

Husband: Col. Rev. Charles Newton King (b. West Point, MS, Feb. 8, 1896-Feb. 28, 1975, Frankfort, KY, Frankfort Cemetery) Parents: John King & Ella Jones

* REVEREND CHARLES NEWTON KING IN FRANKFORT, KY

Due to urban development, in 1966 King led moving the Corinthian Baptist Church to its current location (corner Second and Murray streets) in South Frankfort, Kentucky, built an educational building in 1967, broke ground for a new sanctuary in 1974, and preached there until his death in 1975. The historic parsonage (c.1894) at 216 Murray Street, where Rev. Walker lived, was moved by the Franklin County Trust for Historic Preservation, and now stands restored at 216 E. Second Street across the street from the current Corinthian Baptist Church.

Father: Rev. Junius Franklin Walker (b. Richmond, VA, May 20, 1873-Jan 1, 1957, d. Cinti, Spring Grove) Parents: Emily & F. Walker

Mother: Hattie (Harriet) R. Brown Walker (b. Philadelphia, PA, Oct. 31, 1877-Aug. 10, 1972, d. Cinti, Spring Grove) Married: J. Franklin Walker Aug. 23, 1898, Philadelphia Parents: Robert & Anna Louise Cooper

Sister: Breta Adelaide Walker Grannum (b. Chillicothe, OH, Feb. 14, 1902-Mar. 5, 1991, d. Cinti, Spring Grove) Married: Stanley E. Grannum on March 27, 1931, Cincinnati

NEWSPAPER ARTICLES

The Union: April 3, 1920; May 1, 1920; Oct. 28, 1920; Jan. 22, 1921; April 19, 1921; May 28, 1921; June 18, 1921; July 23, 1921; Aug. 20, 1921; Feb. 4, 1922; March 12, 1922; May 20, 1922; June 17, 1922; Sept. 2, 1922; Oct. 7, 1922; Jan. 13, 1923; May 26, 1923; June 9, 1923; June 16, 1923; March 1, 1924; Sept. 6, 1924; Oct. 11, 1924

Cincinnati Enquirer: Nov. 22, 1924; Feb. 11, 1928; March 18, 1929; March 31, 1935; Feb. 23, 1936; Nov. 26, 1938; Jan. 3, 1957; May 25, 1957; Aug. 12, 1972; Mar 20, 1975; March 9, 1991

Cincinnati Times Star: Feb. 13, 1932; Aug. 25, 1932; Feb. 8, 1933; May 2, 1933; June 7, 1933; June 21, 1933; Dec. 6, 1934; April 17, 1940; Nov. 14, 1942; Oct. 12, 1943; Jan. 22, 1944; May 17, 1950; Dec. 28, 1950

Cincinnati Post: May 26, 1925; Nov. 20, 1929; Nov. 22, 1929; Sept. 14, 1945; Nov. 14, 1955

Cincinnati Commercial Tribune: Oct. 25, 1915; May 26, 1925; Nov. 15, 1927; April 21, 1928; May 26, 1929; Nov. 22, 1929

Cincinnati Herald: March 6, 1965

Indianapolis Recorder: Nov. 29, 1902

The New York Age: August 31, 1918

REFERENCES

The Cincinnatian, University of Cincinnati Yearbook, 1921, 1922, 1925

University of Cincinnati Record, Series I, July 1921, vol. 17 no. 3, 1920-21

University of Cincinnati Commencement Programs, 1921, 1924, 1940

Woodward High School Yearbook, 1917

Williams’ Cincinnati Directories, 1904-1955

Fisk University News, 1917, v. 7, n. 17

Bacote, Samuel William, ed., Who’s Who Among the Colored Baptists of the United States, v. 1, Franklin Hudson Publishing Co., Kansas City, MO, 1913, p.138-139.

Sarna, Jonathan D. and Nancy H. Klein, The Jews of Cincinnati, Center for the Study of the American Jewish Experience, Young and Klein Technicraft, Inc., Cincinnati, 1989.