By Thea Tjepkema

…let us think, as we lay stone on stone, that a time is to come when those stones will be held sacred because our hands have touched them, and that men will say as they look upon the labour and wrought substance of them, "See! This our fathers did for us."

–The Seven Lamps of Architecture, John Ruskin

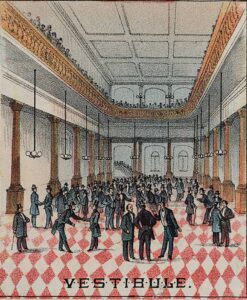

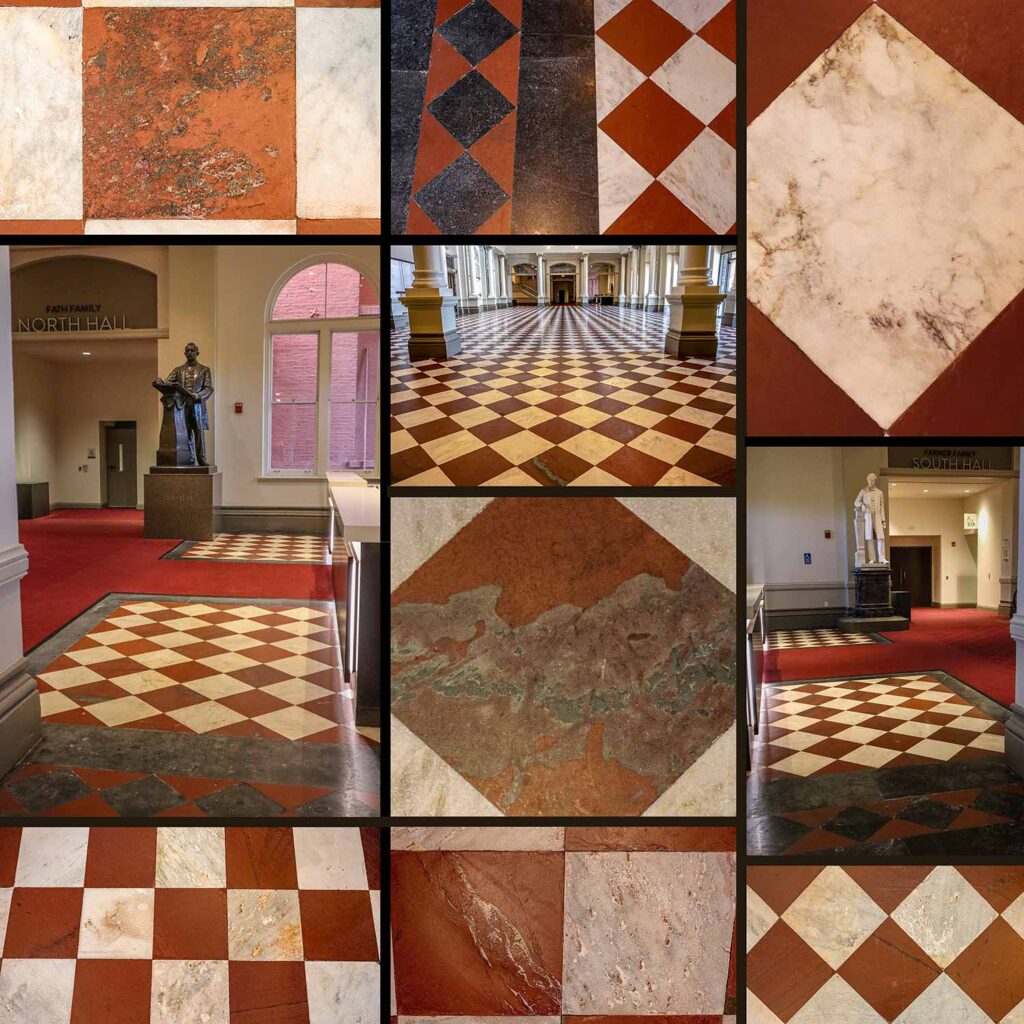

The Friends of Music Hall has funded the preservation and restoration of Music Hall's red, white, and black stone lobby floor – for the first time in 146 years. The diamond-shaped geometric pattern in red slate and white marble bordered by black limestone is the most stunning 1878 interior architectural feature of this National Historic Landmark. It has gloriously welcomed visitors entering Music Hall since 1878 when the May Festival program described it as "a royal approach to the auditorium beyond ... a beautiful waiting place to take off your wraps ... where persons may promenade ... eminently characteristic of the whole structure and its conception."

Architect Samuel Hannaford chose rich polychrome High Victorian Gothic colors on the interior and exterior of this monumental building. The stone tiles of the Edyth B. Lindner Grand Foyer and flanking lobby areas in the north and south corridors match exterior architectural materials of red pressed brick, black decorative brick, and light sandstone. Hannaford also chose these stones for their durability and natural luster, and they were cut and set with extremely tight joints by the leading stone business in Cincinnati in the 19th century, owned by a fellow English immigrant, Isaac Graveson.

This recent extensive restoration occurred between July and August 2024 by experts using preservation technology to repair over 7,000 cracks, chips, holes, pitting, crazing, and spalling, returning the original seamless elegance of Cincinnati Music Hall's most splendid remaining interior space that has not changed since 1878. Millions of people from all walks of life have celebrated and socialized atop these stones, wearing various shoe styles, and they continue to gather here on a magnificent and solid foundation.

INSPECTION BY A STONE CONSERVATOR

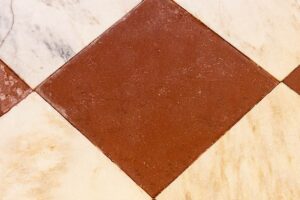

In May of 2023, FMH funded an inspection of the tiled floor by historic stone conservator Frederick Hueston of Stone Forensics, Inc. (Melbourne, FL). He identified the stones as quarried in Vermont: Unfading Red Slate, Danby White Marble, and Champlain Black Marble (limestone) and laid without mortar joints onto a 3-inch thick mortar substrate. Hueston recommended removing layers of modern acrylic finish coatings, wax polishes, and numerous faulty repairs or poorly color-matched fillers. He identified hundreds of damaged tiles, compromising their structural integrity, safety, and the overall aesthetic appearance of the floor.

STONE RESTORED & PRESERVED TO ITS ORIGINAL ELEGANCE

An expert team from Eighth Day Stone Restoration (Charlotte, NC), a leading professional stone restoration and preservation company, began methodically working on a tiled section in the south corridor in front of the east-end bar, working northward in 30-foot square sections through the central grand vestibule (46 feet wide x 112 feet long x 41 feet high), to the north corridor in front of the east-end bar. For decades, the checkerboard red and white pattern spanned the entire width of the corridors, from the front of each of the corridor's matching grand staircases, which had stone steps with cast iron railings painted with mahogany graining.

Library of Congress.

Home Beautiful Exposition.

Coal Convention & American Mining Congress Expo.

with carpet and glass doors.

The south grand staircase was removed in the 1970s and replaced by two escalators. During the 2016-17 renovation, one new escalator and abutting staircase matched the footprint of the remaining north corridor grand staircase. During that 2016-17 revitalization, a few remaining red and white tiles were discovered under carpeting in the corridor lobbies and saved, and pairs of rectangles or red and white tiles bordered by black stone were placed in front of the north and south bars. Eighth Day Stone removed stubborn carpet mastic from the corridor tiles and then used a conservation-safe water-based acrylic finish remover across the entire lobby, revealing the original natural color of the stones. Most surprising was discovering the gorgeous green serpentine mineral graining in the unfading red slate that over the years, turned dark gray.

matches color to use to repair a tile.

After removing the wax and acrylic coatings, the correct colors could be matched for repairs. Joints and mismatching fillers of various epoxies were cleaned out carefully with rotary dremels and chisels. New conservation non-yellowing UV stable urethane filling was mixed and precisely matched using conservation color tints or pigments and applied with putty knives and the skill of Eighth Day Stone’s artists for seamless repairs. After curing, the restored spots were gently sanded to create a naturally blended, smooth, and level finish. The original edges of the diamond-patterned, over an inch thick, 14 x14-inch red and white, and 12 x12-inch red and black border square stones are crisp again. Then, after over 7,000 cracks, chips, holes, crazing, and spalling across the lobby were repaired, a very light buffing of the surface blended the patches and evened out the floor. The stone was protected with an impregnable preservation-safe water repellent, which allows the tiles to breathe – expand and contract. The stone floor looks as new as 1878 and will no longer require abrasive applications of modern acrylic coatings, waxing, polishing, or heavy honing, which dangerously chips corners and edges, scratches surfaces, and rapidly thins the stones. The natural glowing luster, chosen for Hannaford’s intended design and cohesive appeal, can now be maintained with dust and damp mopping – solidly lasting another 150 years or more to embellish Music Hall.

BEAUTY IN STONE NEWLY REVEALED

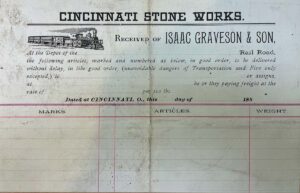

ISAAC GRAVESON & CINCINNATI STONE WORKS

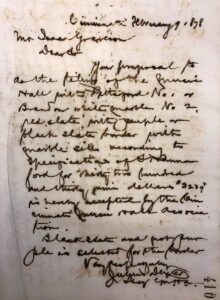

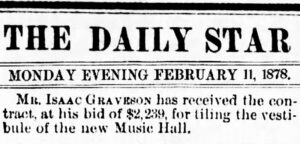

Isaac Graveson and his Cincinnati Stone Works received the contract for tiling Music Hall in a letter written on February 9, 1878. Julius Dexter, secretary and building committee chair of the Cincinnati Music Hall Association (CMHA), wrote to Graveson that he “herby respected” his proposal for tiling Music Hall with Pittsford No. 1 or Brandon white marble No. 2, red slate with purple or black slate border with marble sills “according to the specifications of S. Hannaford” for $3239.

Quarries for white marble and red slate were in Pittsford and Brandon, Vermont. It is unknown if the purple or black slate with marble sills was in the lobby area – perhaps in the original entryways, which have had the stone removed over the years. The existing black border stone is from the Champlain Valley region of Vermont and is often called marble but is a limestone – look for fossils in shell shapes (Gastropods-snails & slugs) in the black stone border.

Two days after Dexter’s letter to Graveson, The Daily Star reported he received the contract for the bid to tile the vestibule of the new Music Hall, but the Cincinnati newspaper’s total was off by a thousand dollars. The CMHA account or cash book, kept by John Shillito, Treasurer (1877-1879), notated payments to Graveson for “Tiling,” first a percentage or deposit in January 1878 of $1,000, then four more payments between March and June, for a final total of $4,264. The floor was ready for the opening of the center hall with its flanking north and south corridors for the Third May Festival on May 14, 1878. The north and south halls, separated from the center hall by carriage passageways, were opened on September 10, 1879, for the Seventh Grand Industrial Exposition.

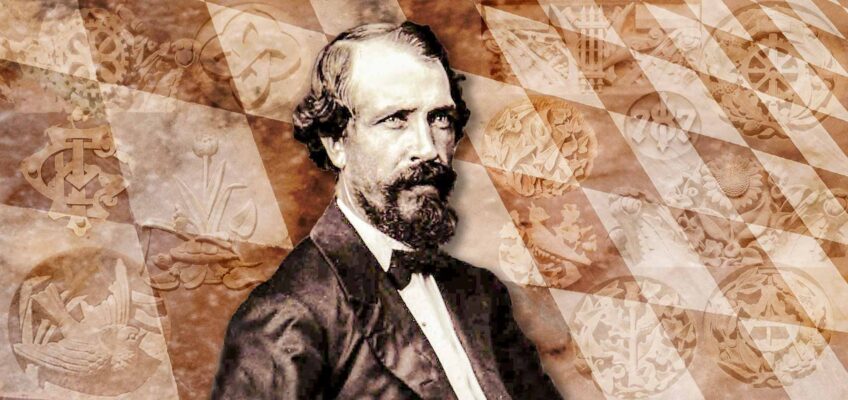

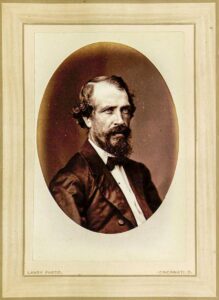

GRAVESON (1826-1903), KNOWN FOR STONE, FAR & WIDE

Isaac Graveson was born in Haxey, Lincolnshire, England, on March 24, 1826. At 14 years old, he began an apprenticeship in stone-cutting and by 17 was recognized as accomplished enough to receive contracts. With £100 in savings ($20K today), he sailed across the Atlantic and landed in New York City on May 10, 1849. Emigrating immediately to Cincinnati, Graveson found stonework in the erection of the Seventh Presbyterian Church on Broadway (Architect: Goodhall, Completed: 1851) and several buildings on entire blocks of Pearl, Columbia, Third, and Fourth streets. Prominent architects and Cincinnatians quickly recognized the rare skill of one of the first stone cutters in the city.

The Danville Tribune, KY, Oct. 30, 1885.

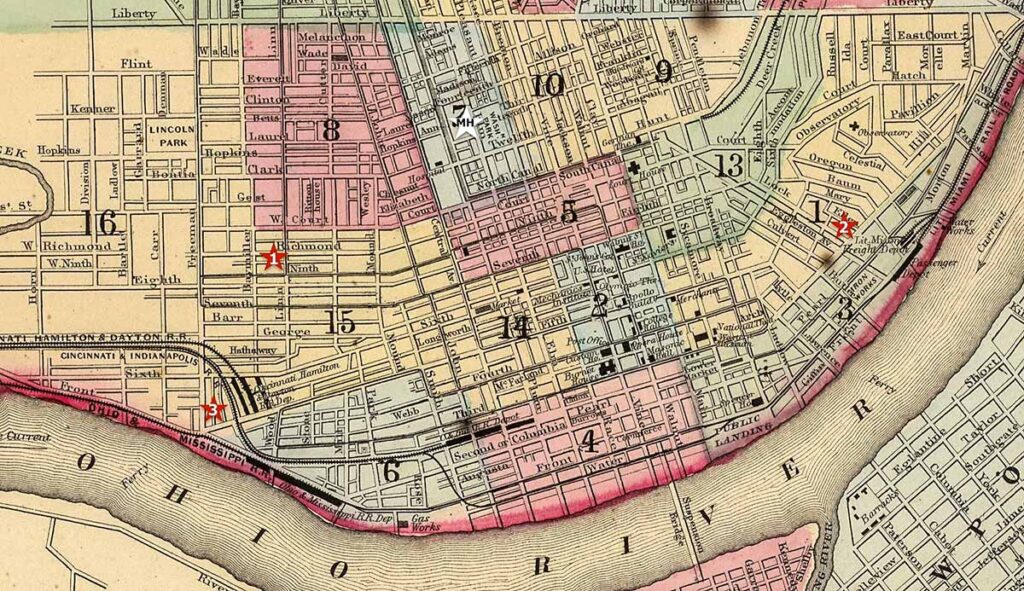

He established his own stone company and branch to deal in stone, located not too far from the canal delivery packets on the Miami and Erie Canal (reaching from Cincinnati to Toledo in 1845), the steamboats for shipping on the Ohio River, and significant freight railroad stations for the ease of receiving and transporting stone.

He quickly became known across Ohio, the Midwest, and beyond for his stonework, which he shipped to Dayton, OH, and Columbus for the Ohio State House; Covington, and Louisville, KY; St. Louis, MO; Indianapolis, IN; Memphis, TN; Cairo, IL Custom House and Chicago for the Chamber of Commerce; St. Paul, MN; and Canada.

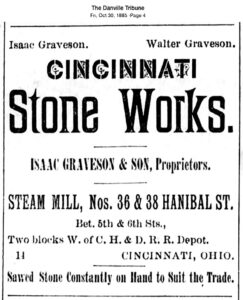

GRAVESON STONE COMPANIES BY MANY NAMES FROM 1851 to 1903

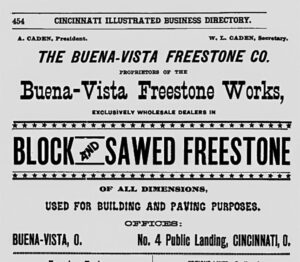

Isaac Graveson became known as one of the best dealers, contractors, and cutters of freestone in the West. His first business opened in 1851, Isaac Graveson and Co., at the corner of Richmond and Linn streets (1.), on the west side of Cincinnati, a mile north of the Ohio River and the Hamilton & Dayton Railroad Depot. In 1856, he leased a mill from Nicolas Longworth on the east side of downtown. He partnered with Buena Vista Freestone Company (sandstone quarried 100 miles up the Ohio River on the western border of Scioto County, today Stout, Ohio, with an office in Cincinnati). After dissolving the partnership, he renamed his business Graveson and Co. (1858-1861), still located on the southeast corner of Third and Lock (2.) streets a block from the Ohio River, the Miami and Erie Canal, and Little Miami R.R. depot. When his nephew William Graveson joined him, the company became I. & W. Graveson from 1861 to 1874, then William Graveson & Co. opened a Freestone Works at 130 Hunt Street, and after 1862, Isaac opened a new branch on the west side at Hannibal Street between Fifth and Sixth (3.) streets while living nearby at 286 Richmond Street. Graveson's Cincinnati Stone Works was located at 36 & 38 Hannibal (today in the block of land bordered by Fifth St., Sixth St., Linn St., and Freeman Ave.) from 1875-1883.

Between 1877 and 1879, Music Hall was constructed a little over a mile northeast of Graveson's west-side stone works; therefore, stones were most likely delivered there by horse-drawn dray carts – listed at a hundred dollars a piece in his inventory. (No photos of Music Hall under construction have been found.) Finally, in 1884, when his son Walter Henry Graveson officially joined the company, it became Isaac Graveson & Son. Isaac Graveson's companies – contractors in cut stone and dealers in sawed stone – were described as one of the country's most complete and extensive businesses. Graveson ran his stone business for 52 years in Cincinnati until his death on September 19, 1903.

STONE ON MUSIC HALL FAÇADES

Isaac Graveson supplied most of the stone on Music Hall, including finials, recently restored by the Friends of Music Hall. Seven finials are on the last page of eight dedicated to stone supplied to Music Hall in Graveson’s Estimate Book in 1876. Their height and width closely match the three in front of the Rose Window and two each on the north and south corridors on the east and west façades. Whether Graveson carved the finials and the sandstone lyre above the datestone or a sculptor in his company is unknown. The CMHA Annual Report of the Trustees of 1877 reported that “Cut Stone Work” awarded to Isaac Graveson would equal $22,800. The stone carver or supplier for the four finials on the 1879 north and south wings is yet to be determined. However, in April, June, and October of 1879, J.R. Laube Cut Stone is the highest-paid stone supplier in the CMHA account books. John R. Laube, in the 1879 Williams’ Cincinnati Directory, owns Laube & Co. Steam Stone Works, 485, 487, 489, 491, and 493 Plum Street.

GRAVESON ORDERED STONE FROM ACROSS THE COUNTRY

Cincinnati Illustrated Business Directory, 1888-89.

The eight-page list of stones supplied to Music Hall in Graveson’s estimate book totals $23,600 ($742,000 today). The Music Hall stone list includes strings and belts (courses), balcony floors and platforms, steps, sills, mullions, transoms, pedestals, plinths, moldings, corbels, capping, gable coping, ceilings, platforms, oriels, carved caps, keystones, blocks, round panels, square headers, arches, gutters, water table, cellar caps, and a carved date stone. Graveson’s records show he ordered stone from throughout the Midwest region, from the east coast, and as far south as Georgia, delivered by rail from several quarry businesses: Columbia Stone; White Stone Quarry Co., KY; J. McDermott and Co., Cleveland Sand Stone; E. Walker Limestone; Adams Au Sable; Portage Red Stone Co.; Beauford Stone, Amherst; Boyer and Corneau Lime Stone; Southern Granite Co.; Earnshaw Worthy & Co.; Bedford Bluestone and Freestone, IN; Bowling Green Limestone; W.W. Lowe; Big 4 Lime Stone; Scanlon J.L.; and Buena Vista Stone Co.

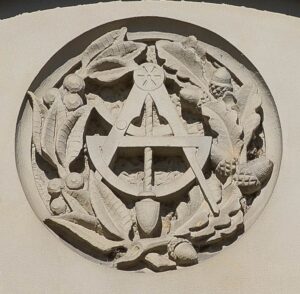

DECORATIVE DETAILS CARVED IN SANDSTONE

The decorative stone carvers who worked on Music Hall seem anonymous. However, Graveson’s estimate book includes the date stone carved with Gothic numbers 1878. There are two date stones, one centered on the front/east façade and another on the back/west façade in carved sandstone. Many more decoratively carved sandstone details are on Music Hall, and most likely, the stone and carvers supplied by Graveson. Some adornments are like signage, providing clues about what occurred in each hall. On the center building, opening as “Music Hall,” with the main stage and auditorium hosting large choral festivals, orchestras, and bands, are pilasters with capitals carved with a lyre, horn, clarinet, violin scroll, and bow, and further up on the corridors are medallions with birds singing representing choral music. On the north hall, which opened as Machinery Hall for annual Grand Industrial Expositions, are medallions with a gear and machinist’s ball-peen hammer; survey kit: compass, plumb bob, clinometer; saw blade; and the initials C.I.E. (Cincinnati Industrial Exposition). The south hall, which opened as Horticultural Hall, has C.I.E. in the Gothic arch above the main door and medallions with sunflowers, thistle, and a calla lily. Learn the fascinating symbolism of this stone ornamentation on a Friends of Music Hall tour on the outside of the building – Beyond the Bricks: Architectural Tour.

PROMINENT BUSINESSES & HOMES USE GRAVESON’S STONE

Graveson’s company cut, sawed, and carved architectural building stone and details that adorned many prominent Cincinnati businesses, including Calvary Episcopal Church (Clifton, Hannaford, 1867); The Allemania Society (Fourth St. & Central Ave., McLaughlin, 1878), a property built for Music Hall’s major benefactor Reuben R. Springer; Spring Grove Cemetery Chapel and Lodge, office building at entrance (Hannaford & Sons, 1880); Cincinnati Art (Academy) Museum (McLaughlin, 1886); College Hill Town Hall (Hannaford, 1886-87), Glendale Lyceum (H. Neill Wilson, 1891) and Union Baptist Church (Richmond & Mound streets, Arthur Giannini & E.H. Moorman, Philip B. Ferguson-construction manager, 1894-95).

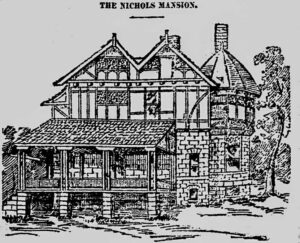

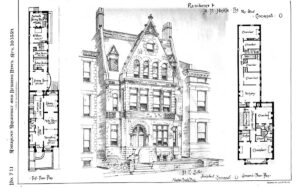

Graveson’s stone decorated over 60 homes of Cincinnatians whose families were involved in Music Hall, including Henry Probasco (“Oakwood,” Clifton, Tinsley, 1859-1866); Marcus Fechheimer (22 Garfield Place, Anderson & Hannaford, 1861-62); George W. McAlpin (“Sunflower Place,” 330 Lafayette Ave., Clifton, Hannaford, 1879); Mrs. George Ward Nichols, Maria Longworth (“Gray Stone Mansion,” 2342 Grandin Rd., second home addition, Hannaford with Maria Longworth, supervising architect, 1885); Alexander McDonald (“Dalvay,” 3689 Clifton Ave., only gates remain, Hannaford, 1881); William S. Groesbeck (“Elmhurst,” E. Walnut Hills, today Hyde Park, Grandin Rd., McLaughlin, 1870-72); John Shillito (Oak Street & Imogene Ave., today Highland Ave., Mt. Auburn, McLaughlin, 1866); and A.H. (Howard) Hinkle (77 Pike St., H.E. Siter, 1889).

HANNAFORD & GRAVESON BACK HOME IN ENGLAND ON TOUR

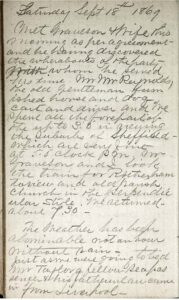

Graveson supplied stone for many of Samuel Hannaford's buildings. They were both immigrants from England. From September to November 1869, Hannaford toured England, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and France. In England, he visited relatives, museums, and cathedrals and took detailed notes on the architectural building styles and materials he admired. In his diary, he mentions the sandstone and freestone and bright cherry red pressed brick (9" x 3" x 4") with blue-black mortar and close joints at ½" depth (like Music Hall's original front façade brick and mortar) in the "Victorian Style." Hannaford meets Graveson "per agreement" on several occasions to tour architecture. Graveson is traveling with his pregnant wife (Sarah). England's latest High Victorian Gothic style was prevalent, and both men were inspired. Polychrome building materials in red, black, and tan were on the exteriors and floors of English churches, and they came home to reproduce them in U.S. stone.

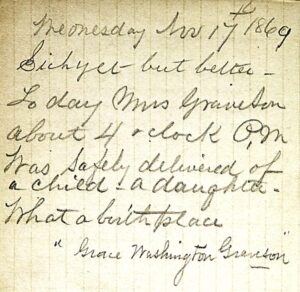

Hannaford toured Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool, and London and got closer to several European city's architecture before sailing back to New York on November 23. Before arriving home, Hannaford’s diary entry on November 17, 1869, noted that at 4:00 p.m. on board the ship, Mrs. Graveson gave birth to Grace Washington Graveson.

GRAVESON’S FAMILY

Isaac Graveson married Sarah Corke (born in Kent County, England) in Cincinnati on Christmas day in 1852. They had nine children, six between one and 15 years old when they moved into their home in 1871 adorned in Graveson's stone on Mt. Auburn (2343 Auburn Ave.) and lived there for four years. Isaac and his family lived downtown at 420 W. Sixth Street from 1874 to 1877 when the construction of Music Hall began. In 1878, he moved to Glendale with his wife and five children: Walter, 19; Luella, 14; Ella, 10; Grace, 8; and Alexander, 6. Sarah died in 1891, and Isaac remarried Eleanor T. Corke (b.1850) in Niagara Falls, New York, on September 30, 1896, and she moved into their home with the three girls. Walter's falling out with his father and leaving the company in 1889, returning to run the company in 1892 and leaving again in 1900, led to litigation over Isaac's will after he died in 1903. Eleanor Graveson moved to Toronto, Canada, and died on February 23, 1936. She is buried in Toronto, although Isaac's will expressed that he wanted her buried with his family in Spring Grove. Ironically, the Graveson family members have simple headstones in Spring Grove Cemetery.

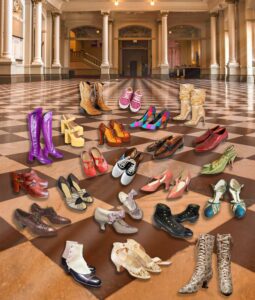

DECADES OF SHOE STYLES & COMMUNITY ON HISTORIC STONE

With over 300 shoe retailers in the city’s directory in 1878 to shop, Music Hall opened with the Third May Festival with almost 6,000 pairs of Victorian men’s and women’s leather buttoned-up boots or satin or kid leather evening slippers with ribbon laces.

By the turn of the century, audiences in the lobby saw men in low Oxfords and women comfortably strolling in Gibson Girl shoes with wide laces. In the 1910s and 1920s, t-strap heels and spats walked into the Springer Auditorium to see Isadora Duncan dance, Mamie Smith "Queen of the Blues" sing, and explore Fall Festivals and Auto Shows. Mary Janes to Saddle Shoes danced to jazz and swung to Edward "Duke" Ellington's Orchestra in the ballroom. The 1940s pumps and wingtips crossed the floor to explore the WWII Exhibition and see Ezzard Charles the "Cincinnati Cobra" box in the North Hall Sports arena or inside the auditorium to see guest conductor Leonard Bernstein lead the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra (C.S.O.). In the 1950s, loafers and kitten heels met up and went inside to hear the singing of Nat King Cole, Marian Anderson, or Fats Domino or to stroll and shop at the Home Shows. 1960s go-go boots gathered for Aretha Franklin on tour or Nina Simone with the C.S.O. In the 1970s, clogs and high platform shoes rocked to Elton John, the Cincinnati Pops featuring Ella Fitzgerald, twirled to the Cincinnati Ballet's Nutcracker, swayed to the cello of Yo-Yo Ma with the C.S.O., or Kathleen Battle in a Cincinnati Opera. Neon pumps or slouchy boots in the 1980s gathered before, during intermission, or after Gladys Knight and the Pips or legendary Metropolitan opera star Florence Quivar with the May Festival. In the 1990s, chunky heels showed up for Diana Ross and cowboy boots for Willie Nelson. The Millennium began with pointy pumps to today's rhinestone sneakers and have partied on the lobby floor for events, concerts, and weddings. The lobby floor will be a robust and beautiful foundation for generations of people wearing stylish shoes for years to come. Think about the shoes and the people visiting Cincinnati Music Hall, walking on this newly restored floor, and the sidewalks around the building admiring Graveson’s historic stone.

…the greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, nor in its gold. Its glory is in its Age and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay, even of approval or condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the passing waves of humanity … it is in that golden stain of time, that we are to look for the real light, and colour, and preciousness of architecture; and it is not until a building has assumed this character, until it has been entrusted with the fame, and hallowed by the deeds of men, 'til its walls have been witness of suffering, and its pillars rise out of the shadows of death, that its existence, more lasting as it is than that of the natural objects of the world around it, can be gifted with even so much as these possess, of language and of life.

– “The Lamp of Memory” The Seven Lamps of Architecture, John Ruskin

Thea Tjepkema serves the Friends of Music Hall Board of Directors as a historic preservationist, historian, archivist, and curator.

THANK YOU to Betty Ann Smiddy for your research assistance and knowledge about architect Samuel Hannaford; Beth Sullebarger for tracing deeds to hunt Isaac Graveson’s home in Glendale; Constance J. Moore for Longworth family research; and Rick Pender, Friends of Music Hall Board for editing.

REFERENCES & BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cincinnati Music Hall Association: For the Year Ending April 30, 1877, Cincinnati, OH, 1877, p. 26. Contracts Awarded: Cut Stone-Isaac Graveson $22,880

Isaac Graveson and Son Collection, 1856-1927, Cincinnati History Library and Archives (CHLA)

Hannford Diaries of European Trips, 1869 and 1901 and Miscellaneous Related Papers, Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library (CHCPL)

Landy, James, Photographically Illustrated, Cincinnati Past and Present or Its Industrial History: As Exhibited in the Life-Labors of Its Leading Men, Cincinnati, OH, M. Joblin & Co., Elm Street Printing Co., 1872. Isaac Graveson Biography pp. 260-262, Photo p. 260a.

Music Hall Cash Book, February 1876-April 1891, Cincinnati History Library and Archives, Collection of the Society for the Preservation of Music Hall, donated in 2002 by board member Bob Howes, Box 59. 1879: Pg. 173 April 26, 1879, Cut Stone JR Laube on a/c $1080; Pg. 179 June 1879 Cut Stone JR Laube on a/c $901 & $510; Pg. 199; October 3, 1879, Cut Stone Work JR Laube on a/c $400.