by Thea Tjepkema

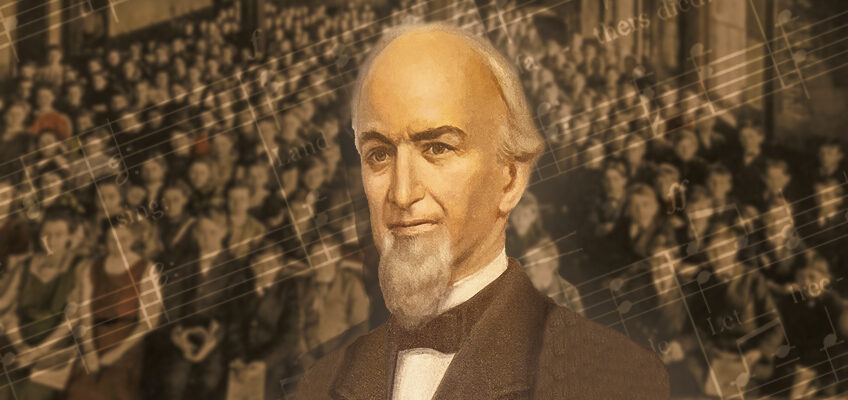

Cincinnati has been a national epicenter for vocal arts traditions for most of its history in large part due to the contributions of Charles Aiken (1818-1882). Aiken developed and taught singing and choral curriculum in Cincinnati public schools for more than 30 years between 1847 and 1878, and became the first titled Superintendent of Music in 1871. In 1884, two years after his death, Aiken’s former pupils, colleagues, and Cincinnati citizens from all walks of life commissioned the marble bust by Preston Powers, still prominently displayed in Cincinnati Music Hall, to memorialize his devotion to choral arts, especially upon the stage of Cincinnati Music Hall, and the deep love of singing that it engendered for generations.

The Musician, May 1906.

Family and Home in Cincinnati and College Hill

Born in Goffstown, New Hampshire, Aiken graduated from Dartmouth College in 1838 and pursued a career in music education. As an itinerant music teacher, he traveled to Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Cincinnati, returning to the east coast in the summer of 1840 to marry Cordelia Butler Hyde in Williamsburg, Massachusetts. They moved to St. Louis where he taught vocal music at a local music academy and served as choir director of the Second Presbyterian Church.

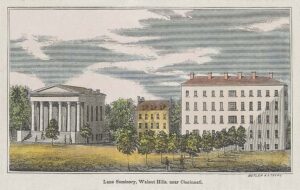

A New & Popular Pictorial Description of the U.S.

by Robert Sears. Butler & Strype, New York, 1860.

Three years later, Charles and Cordelia moved to Cincinnati, where he attended the Lane Theological Seminary. By the time of his 1847 graduation, they had four children, but in 1849 Cordelia died. Soon after, he married her sister, Therese, but she died in 1852. In 1855 Aiken married Martha Stanley Merrill; they had eight children born in Cincinnati.

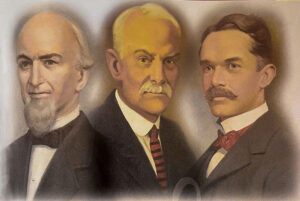

Paintings in Aiken H.S.

A City That Sings, pg. 41.

Aiken’s sons Walter* and Louis** followed in their father’s footsteps as devoted music teachers in Cincinnati Public Schools.

The Aiken family lived in downtown Cincinnati for almost two decades, including six years on the corner of Liberty and Main streets (1858-63). Around 1864 they settled in College Hill, where Aiken died at home in 1882. The Charles Aiken home was razed in the 1960s to make way for the Cross County Highway.

Charles Aiken Vocal Music Teacher in Cincinnati

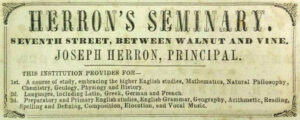

While studying at Lane, Aiken began to devote himself to bettering the lives of young people in Cincinnati. He gave free vocal lessons in a school in the basement of the old Sixth Presbyterian Church (on the south side of Sixth between Main and Walnut streets) introducing the “movable Do system” to adult and young singers beginning in 1843. He also taught Latin and Greek part-time for five years at Joseph Herron’s Seminary on the north side of Seventh between Walnut and Vine.

razed 1872.

After graduating from Lane, Aiken traveled throughout the city as a voice teacher for grades 1-8 (Classes H-A). As part of the public school duties, he also gave lessons at the Cincinnati Orphan Asylum, located on the site of today’s Music Hall. Orphanage records from 1850 show a donation of $200 from Jenny Lind, the famous 19th century “Swedish Nightingale” soprano, likely because she was so impressed with their singing instruction.

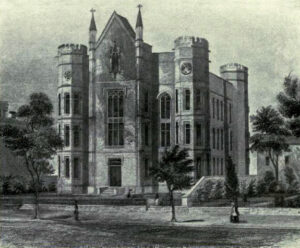

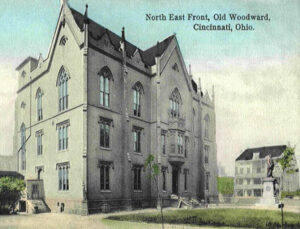

when it was completed in 1853.

2nd Building (1855-1907) by John R. Hamilton

Aiken began teaching at the first high school, Central School (est. 1847) in 1850, the following year at Hughes High School, and two years later at Woodward High School, teaching full-time by 1855. In 1867-68 he also taught music at 646 Main Street.

Aiken helped establish the first rigorous semiannual music examinations for pupils and teachers in 1848 and was a co-examiner during his 30 years of teaching. He also helped compile and edit primary and intermediate music textbooks for Cincinnati Public Schools and created his own collection of choral arrangements for public high school textbooks***.

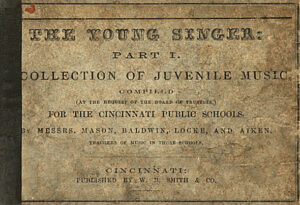

from The Young Singer 1860.

These method books contained exercises and songs, rounds, and hymns, as well as selections of masterworks by Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Rossini, Bellini, and Verdi. They had an appendix with selections “from the German, with original words,” which appealed directly to Cincinnati’s large German population. German-English schools started in churches in the city in 1840. By 1849 German departments were introduced in various public schools.

Music Education in Cincinnati Public Schools

Music education in Cincinnati’s public schools began just a few years before Charles Aiken came to the city. Voluntary instruction in singing started in 1837, eight years after Cincinnati public schools were established in 1829. Interest in creating formal music classes began soon after Lane Seminary professor Calvin E. Stowe and his wife, Harriet Beecher, traveled to Columbus for their honeymoon. While there, he spoke at Ohio’s first educational convention (January 13-15, 1836) about the common schools of Prussia, where children demonstrated the ability to read music and sing at a very young age. Commissioned by the Ohio General Assembly to travel to Europe to study the school systems, Stowe’s report was given to the Western Literary Institute and College of Professional Teachers in 1837, and published encouraging vocal music education in U.S. public schools.

Lowell Mason, Music Superintendent of Boston Public Schools, is often credited with giving the first music lessons in public schools in 1838. However, Lowell’s youngest brother, Timothy Battelle Mason, may have taught free music lessons in Cincinnati public schools a year earlier in an unofficial capacity. T.B. Mason moved to Cincinnati in 1834 to direct The Eclectic Academy of Music (1834-1842), Ohio’s first state-chartered music school, formed one year after the Boston Academy of Music. Both brothers worked to promote public school music instruction by training music teachers.

By 1843, the first volunteer music teachers in Cincinnati public schools were in the annual report as Elizabeth K. Thatcher (1843-46) and William F. Colburn (1843-48), and by the school year, 1844-45 had the first paid contracts. Two students of Lowell Mason in Boston, Mr. Elisha Locke (1846-66) and Miss Solon Nourse (1846-50) succeeded Thatcher. Nourse retired by 1850, and Charles Aiken followed Locke at the Central School. Colburn was a founding faculty member of the Eclectic Academy and also a student of Charles Aiken in the old Sixth Presbyterian Church basement. In 1848, Aiken succeeded Colburn, serving as the acting superintendent, a position he retained until it became a titled position.

Music in Cincinnati’s Segregated Public Schools

From the beginning of the establishment of Cincinnati common schools in 1829, access was denied to African American children. In response, Black community leaders established their own schools. They lobbied for a separate public school system, eventually granted by Ohio state law in 1849. The Independent Colored School System, staffed with Black teachers and principals, received the education taxes of Black citizens. In 1850 the Ohio Supreme Court found that, “colored children could not lawfully be denied the right to attend common schools,” but that “it was unquestionably better to place the youth in separate schools.”

The 1855 First Annual Report of the Colored Common Schools hoped for a permanent music teacher. In the second report in 1856 music instruction was “regularly taught in all the Departments.” The first listing of a white music teacher in Black public schools was in the 1866-67 annual report: Wendell Schiel, born in Alsace, France, who taught from 1865 to 1877.

In 1873 an Ohio law took control away from the Black school board trustees and gave the operation to the white trustees of the Cincinnati Board of Education. Almost all African American children remained in the segregated Black public schools, preferring to be taught by Black teachers. While white teachers could teach in Black schools, Black teachers were not allowed to teach in white schools. The Cincinnati Public School annual reports between 1874-76 list Carl Von Weller as music instructor of the “colored schools” in the Eastern and Western Districts downtown and Walnut Hills (Elm Street School).

Charles Aiken’s schedule for the 1874-75 school year included teaching music at a “colored school” on Thursdays. As Superintendent, Aiken reported that he was “well satisfied with their progress” and in the 1876-77 annual report stated that Black students made “rapid advancement in musical culture” and “a large percentage of their teachers sing and are fond of good music.”

College of Music of Cincinnati, Next Door to Music Hall

The 1879-80 annual report of the public schools reported that the College of Music of Cincinnati (CMC) had opened in August 1878 in Music Hall. It soon had a campus immediately south of Music Hall (today a parking lot). Its establishment was credited to the success of the May Festivals, the presence of Music Hall, and the taste of Cincinnati citizens. But more importantly, all three were due to music being taught in public schools.

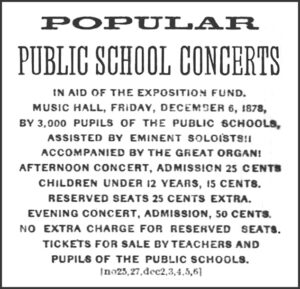

That same year, the Board of Education began a Commission on Music Scholarships for public school students to attend CMC. It included nine members, four from the Board of Education, two from the Union Board of High Schools, and two from CMC (Music Director Theodore Thomas and President George Ward Nichols). The Committee set rules: at least two annual May concerts by public school students held in Music Hall with proceeds supporting a scholarship fund for intermediate and high school students to attend CMC. In May 1878, the public school children gave two concerts for the Scholarship Fund and the Exposition Fund to build Music Hall’s north and south halls.

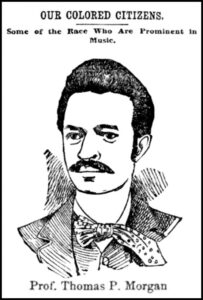

African American Music Teachers in Cincinnati Public Schools

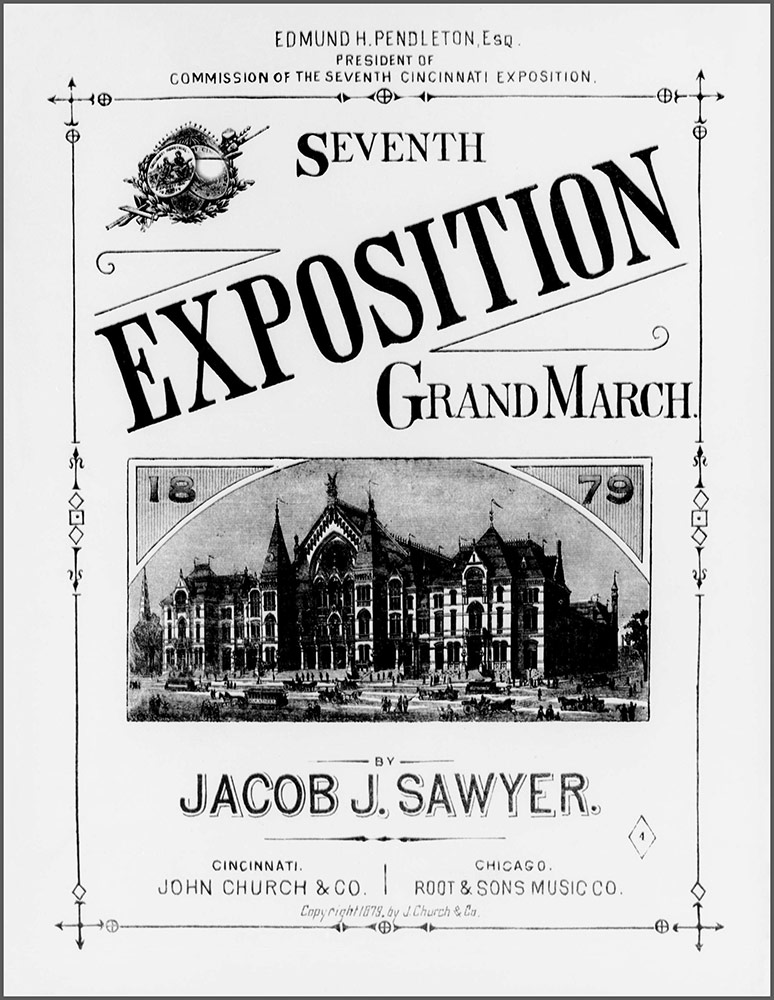

The public school board’s music committee voted in August 1879 for African American Jacob J. Sawyer (1856-1885) to teach music in the Cincinnati “colored schools only.” Sawyer was the accompanist and composer for the Hyers Sisters (1875-79), singers and agents of change in African American musical theater. He moved to Cincinnati in January 1879 and lived in a boarding house at 31 Longworth Street. In hopes of obtaining a teaching position, Sawyer sought the counsel of Theodore Thomas, music director of the May Festival and CMC. He took Thomas’ advice and attended CMC to study music theory and violin.

by Jacob J. Sawyer. John Church & Co.

Library of Congress.

Listen to the Seventh Exposition Grand March

While in Cincinnati, Sawyer’s composition for the Hyers Sisters’ dramatic play, Out of Bondage Waltzes (Op. 2) was published by George D. Newhall & Co., 62 W. Fourth Street. He was also commissioned by Edmund H. Pendleton, president of the Seventh Industrial Exposition, to compose a march for a military band for the opening of the Exposition in the completed Music Hall. His Seventh Exposition Grand March (Op. 3) was published in 1879 by John Church & Co. Listen to the Seventh Exposition Grand March. Even with his experience in music, the public school’s music committee backing, and a nomination from Theodore Thomas, Sawyer did not get a job teaching in Cincinnati public schools. He returned to his hometown of Boston in 1880, where he composed 44 more pieces before his death of tuberculosis in 1885.

The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette,

Aug. 18, 1889, pg. 16.

The first African American music teacher in the Cincinnati Public Schools was Thomas P. Morgan (1854-1924) from 1885 to 1891. He studied music theory under Professor Charles Baetens at CMC and received his teaching certificate from the Board of Examiners of the Cincinnati Public Schools. Born free in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, Morgan moved to Cincinnati in 1874 to work for the Howe Sewing Machine Company. He was a janitor for seven years at the public library, their first Black employee. Morgan was also the music director of choirs at Allen Temple, Union Chapel, and Union Baptist Church. Ohio law in 1887 abolished segregated public schools, but de facto segregation continued for decades.

At the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, Cincinnati Public Schools displayed music textbooks, method books, choral arrangements that Charles Aiken and his colleagues developed, and included work by African Americans at Gaines High School (est. 1866).

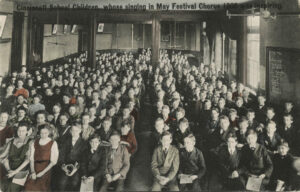

Mass Public School Choirs Sing for the Community

Kraemer Art Co., Cincinnati Memory Project,

Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library.

Aiken was most beloved for assembling and conducting mass choirs of school children throughout the region. Starting with a concert on December 21, 1863, Aiken led 900 high school and intermediate students at Mozart Hall (Sixth and Vine streets) as part of the entertainment for the opening ceremony of the Great Western Sanitary Fair, which raised money for provisions for Civil War soldiers. They sang several patriotic selections and concluded with the anthem “My Country! ’Tis of Thee” with “stirring and powerful volume.”

After the Civil War, Aiken assembled numerous Sunday School choirs to welcome home soldiers at the Eighth Street Park on Independence Day in 1865. Throughout his teaching career, he prepared and conducted public school choruses of 500 to 1,400 children in performances throughout the community. They sang in a benefit concert for the public library at Pike’s Opera House (1862), at the dedication of the Tyler Davidson Fountain (1871), and for the first two May Festivals in Saengerhalle (1873, 1875). Based on his legacy, student choral ensembles became a regular feature of May Festivals in Music Hall starting in 1882, the year of Aiken’s death.

3,000 Public School Children Sing in Cincinnati Music Hall

Music Hall. The Cincinnati Enquirer,

Dec. 6, 1878.

The culminating event of Aiken’s career was two benefit concerts in the city’s new Music Hall on December 6, 1878. Twenty-six public school choirs, totaling 3,000 children, sang to raise funds to support the construction of the North and South exposition wings. Children sold tickets resulting in an audience of 4,900 at the afternoon concert and more than 3,500 in the evening. Prussian-born public school music instructor Henry Brusselbach conducted both concerts. The Cincinnati Commercial mentioned that seven music teachers of the public schools prepared the students: Aiken, Brusselbach, Junkerman, Schmidt, Shiehl, Williams, and Zeinz. The 2 p.m. concert listed 1,500 students from the eighth grade (Class A) and Gaines High School; the 7:30 p.m. concert featured another 1,500 students from the Normal (teacher training) and intermediate schools, Hughes and Woodward high schools.

Aiken attended both concerts and led the evening’s grand finale, “America,” asking the audience to join in singing with the children. He said he had heard them all sing years ago when they were his pupils, and he desired to hear them once again. The concerts raised $3,000 in subscriptions donated toward the Exposition Fund.

Sadly, this heartwarming story was tainted with racism. The 60-member all-Black Gaines High School chorus did not perform in the afternoon concert. They had been given short shrift during the previous day’s dress rehearsal, and withdrew from the concert. A letter to the editor of the Cincinnati Commercial reported the details of the discriminatory event, but a direct apology was not in the press. Nonetheless, the Black high schools Superintendent William H. Parham, Gaines High School Principal Peter H. Clark, and other faculty donated to the Exposition Fund later that month.

It is unclear if Gaines High School was part of the mass public school concert organized for the completed Music Hall grand opening on September 10, 1879, the Seventh Industrial Exposition. The public school children’s chorus opened the ceremony and closed the ceremony with “patriotic airs on the great organ.” The closing number was a familiar national hymn, “Our Native Land,” accompanied by the organ. In the audience was President Rutherford Hayes, who “led well-merited applause.”

Charles Aiken devoted his life to bringing music into the lives of Cincinnatians, and helped shape the ethos of the city for generations to come. He set in motion a comprehensive plan for teaching music to all grades in public schools, including a music curriculum that trained the ears and voices of children from all walks of life, opening their hearts to the greatest choral masterworks.

As Professor and Superintendent, he inspired Cincinnati’s long-lasting tradition to read, sing, and enjoy music. On October 4, 1882, Charles Aiken passed away at his College Hill home, the neighborhood where Aiken High School was named to honor his legacy and that of his sons, Walter and Louis. Charles and his sons contributed a combined total of 126 years of service to music education in Cincinnati Public Schools which continues to resonate throughout the city.

In Aiken’s final Superintendent of Music report of 1878 he wrote,

Music is the children’s best friend, a model of beauty, purity, and holiness. Its moral influence manifests itself in dignifying and ennobling their souls. Let music then be received as a gift to promote our own, but still more our neighbor’s happiness and the art will elevate our hearts, and all our moral affections.

Dedication Ceremony of the Aiken Statue in Music Hall

Music Hall, 2nd Floor,

South Corridor.

Only a few weeks after Charles Aiken’s death, public school principals and teachers met to raise money, naming the fundraising group the Aiken Memorial Association. Intending to place a monument to his memory in Music Hall, they commissioned renowned sculptor Preston Powers. Two-thirds of the funding came from officers and teachers, and the remainder from former pupils and friends.

By June 1884, Powers had completed the Aiken bust, shipped from his studio in Italy. A thousand people gathered on Saturday morning, November 15, 1884, in the vestibule of Music Hall for the dedication ceremony. The statue was draped with a cloth and placed in the main lobby niche, south of Power’s Reuben Springer statue. The ceremony began with Currier’s Band performing Mendelssohn’s Ruy Blas Overture, followed by Rev. George Hammell’s invocation and the music of Rossini. Noble K. Royse of the Sixth District School delivered the memorial address.

We tangibly remember one, who, in his day … prepared the minds and hearts of many … the ears of the vast auditory to an appreciation of the splendid.

Noble K. Royse

Aiken Statue Address

This noble building is most empathically Music’s own shrine … it is eminently proper … in the vestibule of this temple we should be reminded of one, who, in his day, rendered signal service … with the statue of that princely lover and patron of music Reuben Springer … this proud edifice is a Temple to Music (which) will also be acknowledged as the Parthenon of the musical celebrities of the Queen City.

*Walter Harris Aiken (1856-1935) began teaching music in Middletown, Ohio, in 1874. In 1876 he became a supervisor of music for Hamilton, Ohio, and in 1879 began teaching music in Cincinnati Public Schools under his father and G.F. Junkerman, and continued teaching until 1903. In 1900 became the third titled Superintendent of Music in Cincinnati Public Schools (1900-1929) after G.F. Junkerman. He was a chorus director, an editor, and orchestrated 200 works in The Willis Collection of School Songs, used by the University of Cincinnati. He conducted public school mass choirs in Music Hall on several occasions, including at the Golden Jubilee in 1928, the visit of President Wilson, on October 26, 1916, and high school commencement exercises. He was an avid botanist and served five years in the Cincinnati Natural History Society and 25 years with the Lloyd Library overseeing the 40,000 plants in an herbarium. In 1925 he received an honorary doctorate, Doctor of Pedagogy, from the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music-CCM.

**Louis Ellsworth Aiken (1861-1949) began teaching music in Cincinnati public schools in 1880 in Avondale for two years, then in 1886 for Cincinnati Public Schools until 1920; 45 years total, with the last 30 in high schools. He conducted several public school mass choirs in Music Hall, including an 1895 Decorations Day service and high school commencement ceremonies. He organized Cincinnati’s first high school band at Hughes in 1919. He was an itinerant music instructor, like his father, taught at Woodward High School and the Fourth Intermediate School, and was on the faculty at Hughes High School until he retired in 1931.

***The first music books in Cincinnati schools were William B. Bradbury’s The School Singer, or Young Choir’s Companion (1841) and Timothy B. Mason’s Juvenile Harp (1846). The first music books compiled by Cincinnati music teachers Mr. Elisha Locke and Miss Solon Nourse, The School Vocalist, Containing a Thorough System of Elementary Instruction in Vocal Music, with Practical Exercises, Songs, Hymns, Chants &C., Adapted to the Use of Schools and Academies (1848), and The School Melodist: A Songbook for School and Home (1854). Aiken co-authored the elementary school music books known as The Cincinnati Music Readers or The Young Singer: A Collection of Juvenile Music (1860) and for higher classes, The Young Singer’s Manual (1866), as well as two anthologies for high schools, which he authored, but did not take credit, The High School Choralist (1866) and The Choralist’s Companion (1872). Later, John Church Company published a revised series of The Cincinnati Music Reader (1875) for the Board of Education.

Thea Tjepkema, Historian and Archivist, Friends of Music Hall

Tjepkema has created two Speakers Series presentations: Under One Roof: The African American Experience in Music Hall and Muses: The Women of Music Hall. Contact us by email or by calling (513) 744-3293 to schedule a presentation for your group or organization.

THANK YOURick Pender, Friends of Music Hall board member, for your editing expertise.

Geoffrey Sutton, Walnut Hills Historical Society, for sharing your research on Cincinnati’s Black public schools.

John Morris Russell for your steadfast assistance and inspiration.

REFERENCES

Aiken, Charles; D.H. Baldwin, Elisha Locke, Luther Whiting Mason, The Young Singer: Part I: Collection of Juvenile Music, Compiled at the Request of the Board of Trustees for the Cincinnati Public Schools by Messrs. Mason, Baldwin, Locke, and Aiken, Teachers of Music in Those Schools, Cincinnati, Published by W.B. Smith & Co. and Sargent, Wilson, & Hinkle, New York, Clark & Maynard, 1860.

Luther Whiting Mason (1818-96), studied with Lowell and perhaps related, taught in Cincinnati schools 1856-64.

Dwight Hamilton Baldwin (1821-99), studied at Oberlin College, taught in Cincinnati schools from 1857-64; he retired and founded Baldwin Piano Company.

Aiken, Charles; J.P. Powell, Alfred Squire, Victor Williams, The Young Singer’s Manual, Cincinnati, Van Antwerp, Bragg, 1866. Used in Cincinnati Public Schools until 1882.

Aiken, Charles, The High School Choralist, Oliver Ditson & Co., Boston, 1866.

Aiken, Charles, The Choralist’s Companion, John Church & Co., Cincinnati, 1872.

Aiken, Walter H., Music in the Cincinnati Schools, The Musician: For Teacher, Pupil, and Lover of Music, Oliver Ditson Co., Boston, v.11, no. 5, May 1906.

Bertaux, Nancy and Michael Washington, The “Colored Schools” of Cincinnati and African American Community in Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati, 1849-1890, The Journal of Negro Education, v.74, n.1, Winter, 2005.

Birge, Edward Bailey, History Of Public School Music In The United States, 2nd ed., Oliver Ditson Co., Boston, 1937.

Dickey, Frances M., The Early History of Public School Music in the United States, Kent, Ohio, Studies in Musical Education History and Aesthetics, Eighth Series, Papers and Proceedings of the Music Teachers’ National Association at Thirty-Fifth Annual Meeting, College of Music, Cincinnati, Ohio, December 29, 1913 to January 1, 1914, Published by the Association, Editorial Office, Hartford, CT, 1914.

Gary, Charles L., Charles Aiken (1818-1882): Pioneer Apostle of Quality Music, The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education, Sage Pub., v.7, no.1, Jan, 1986.

Lenzo, Terri Brown and Craig Resta, Two Brothers, Two Cities: Music Education in Boston and Cincinnati from 1830-1844, Contributions to Music Education, v. 38, n.1, Ohio Music Education Association, p.27-43.

Osborne, William, Music in Ohio, Chapter 7, Public School Music in Cincinnati, The Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2004.

Pendle, Karin, A City That Sings: Cincinnati’s Choral Tradition 1800-2012, Ch. 2, Queen City of Song Choral Music In Cincinnati’s Schools, Conservatories, and Universities, pp. 32-101, Orange Frazer Press, Wilmington, OH, 2012.

Royse, Noble K., Charles Aiken: An Address Delivered in Music Hall Nov. 15, 1884: At the Unveiling of the Aiken Memorial by Noble K. Royse, Cincinnati, Robert Clarke & Co., 1885, pgs. 1-22. Library of Congress, Rare Books, Special Collections, RRLJ239.

Paul D. Sanders, Calvin E. Stowe’s Contribution to American Music Education, Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, v. 24, n. 2, April 2003.

Sawyer, Jacob, 7th Exposition Grand March, John Church & Co., Cincinnati, 1879, Notated Music, Library of Congress, Music Division, Music for the Nation: American Sheet Music, Ca. 1870-1885.

Schüler, Nico, Jacob J.A. Sawyer, Groves Music Online, Nov. 26, 2013.

Soriano, Constantine F., Cincinnati Music Readers, Master’s Thesis, College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, 1957.

Shotwell, John B., A History of the Schools of Cincinnati, Junkermann, G.F., Chapter 18, Music in Public Schools, The School Life Co., Cincinnati, 1902.

Gustavus Frederick Junkermann (1830-1906), born in Bielefield, Westphalia, Germany; involved in the revolution of 1848, came to Cincinnati in 1849; first taught German in the Jewish schools; taught in Cincinnati schools in 1855; left to perform cello in orchestras in St. Louis, Memphis, and New Orleans; returned to Cincinnati in 1872 teaching part-time, staff in 1873; succeeded Aiken at Hughes and Woodward in 1878; followed Aiken as Superintendent in 1879-1900. He led school choirs at Saengerfests, May Festivals, Expositions, and public concerts.

Annual Reports of the Board of Directors of the Colored Public Schools, 1855, 1856, 1866-67, 1876-77

Cincinnati Board of Education Annual Reports of Cincinnati Public Schools, 1848-1892

Cincinnati Commercial: 12-22-1863, 7-6-1871, 12-11-1878, 08-18-1889

Cincinnati Daily Gazette: 8-16-1879, 8-26-1879, 9-1-1879

Cincinnati Enquirer: 6-28-1865, 10-31-1871, 8-29-1874, 8-29-1876, 9-19-1876, 8-28-1878, 12-6-1878, 10-5-1882, 10-15-1882, 4-27-1884, 6-1-1884, 11-17-1884, 6-29-1949

St. Louis Directories 1840-42

Williams’ Cincinnati Directories 1849-80