by Thea Tjepkema

For more than 140 years Music Hall has been considered the epicenter of Cincinnati’s orchestral and choral music culture, yet the last hundred years at Music Hall also nurtured the rise of American popular music.

By the first decade of the 20th century, the tradition of industrial expositions held in Music Hall had passed, and the north and south exhibition halls were revived as places for social dancing. Regular appearances of African American performers gradually made the Greystone Ballroom a more welcoming place for Black Cincinnatians.

The history of Music Hall’s entertainment spaces is difficult to piece together — primary sources that fully describe the myriad of activities are difficult to find. Nevertheless, it appears Music Hall was not immune to the realities of Cincinnati’s segregated past.

Today we can recognize Music Hall not only as a performance venue, but as a place where our society moved forward, however slowly, towards inclusion through popular music, dance, and entertainment.

1917-1927: Danceland

Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library

Although Music Hall hosted social dances from its very beginning, the North Hall was the first to be converted into a dance ballroom. For the decade between 1917 and 1927, the first floor of the North Hall served as a 27,000-square-foot “big dance palace” called Danceland, the largest popular dance locale of the era. Sibcy’s Danceland Orchestra regularly played society music in a permanent band shell while dancers waltzed and fox trotted to “melody jazz,” light classics, and popular music of the day including patriotic songs during World War I. Often, prizes were awarded to the best dancers, such as “fowl of all kinds” during the holidays and gifts for ladies on special nights. The dancing seasons were highlighted with thematic decorations and renowned soloists.

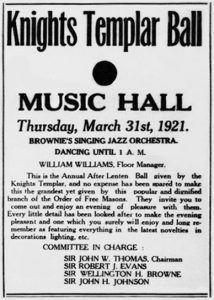

Though not advertised as such, the vast majority of events at Danceland were for white patrons only. However, Cincinnati’s Black newspaper, The Union (1907-1952), in the “Masonic News” column on the front page of April 9, 1921, announced that the Freemason’s Annual Ball of the Simon Commandery of Knights Templar at Danceland had been a success both financially and artistically on March 31. “The Sir Knights and their ladies assembled in beautiful Danceland, Music Hall, and ‘tripped the light fantastic’ to the music of Brownie’s Singing Jazz Orchestra.” In the fall of 1927, Danceland moved from Music Hall to a new location in the Greenwood building at 6th and Vine in downtown Cincinnati.

The Union, March 26, 1921

1927 Music Hall Remodel: Greystone Ballroom & Sports Arena

In 1927 Music Hall embarked on a major renovation, including a 6,000-seat sports arena in the North Hall with east and west end balconies and, in the South Hall, a second-floor ballroom. Music Hall’s Greystone Ballroom opened the evening of January 25, 1928 and was heralded as America’s largest dance floor at 22,841 square feet, with ample room for 5,000 to dance on its curly-maple floor. On the same evening in the North Hall, the new Music Hall Arena opened with boxing matches; the main event was between Cincinnati welterweight Tony LaRosa, and Pittsburgh’s Johnny Windsor, protégé of the “Human Windmill,” Harry Greb. Boxing matches continued into the 1950s in the arena, frequently featuring prominent Black pugilists, including world champion Ezzard Charles.

1928-1935: Greystone Ballroom

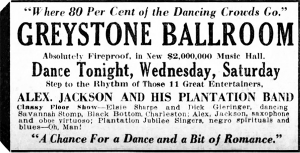

Cincinnati Enquirer, October 13, 1932

Music Hall’s Greystone was most likely named after Detroit’s famed Graystone (named for its gray terracotta façade, and spelled with an “a”), which opened in 1922 with room for 3,000 dancers. Detroit’s Graystone was a proving ground for early big bands: It had two bandstands to allow for continuous music, with one band playing when the other took a break.

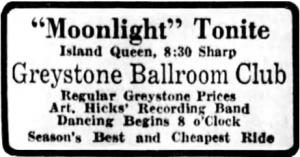

When it opened, Music Hall’s Greystone Ballroom (with an “e”) featured dancing on Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday nights from autumn through spring. During the hot summer months, most of the regular dances continued as the “Greystone Club” on the Island Queen riverboat with “Moonlight Cruises.”

Cincinnati Enquirer, April 8, 1929

During this time, many dance venues including Music Hall’s Greystone, Detroit’s Graystone, and New York’s Cotton Club, were open primarily for white audiences only, though they frequently featured Black big bands, singers, and floor shows. Although virtuosic performances invariably opened many ears and hearts to the sophistication of Black culture, Black performers were often compelled to portray happy and simple stereotypes to ingratiate themselves to white audiences. Dances usually ended at 2:30 a.m. and typically, Black bands would head out after performing to play at “Dawn Dances” where Black dancers were welcome lasting until 8 a.m. In Cincinnati there were Dawn Dances in the Manse Hotel and the Sterling Hotel basement ballrooms, where traveling Black musicians also found safe lodging.

Cincinnati Enquirer, February 26, 1928

The Greystone’s opening in 1928 featured the all-white, 11-piece “Greystone Orchestra,” but to keep the crowds coming, Greystone manager A.E. Scheffer headed to Chicago, Detroit, and New York City to find the choicest bands in the hottest clubs for his Cincinnati venue. Territorial bands were also booked at the Greystone, traveling town-to-town through one or more of seven routes: Midwest, Northeast, Southeast, Southwest, West Coast, Northwest, and the “Military Territory” — U.S. officer’s clubs and overseas bases.

“Missouri Squabble,” Gennett Records.

Many of the Black Midwestern bands began in Springfield, Ohio, just north of Wilberforce University, where there was a great pool of educated professional musicians. Burgeoning musicians could earn money while hoping to make a name on the territorial circuit and eventually join nationally prominent bands. The first “Jazzopathic Melodies” were performed in the Greystone by Alexander Jackson’s Plantation Band, from the original Plantation Inn, a Black nightclub in Harlem’s Lenox District in New York City, famous for its female dance troupe, “The Blackbirds.”

Jackson’s band accepted an offer to temporarily quit the territorial circuit and play exclusively at the Greystone between February and March 1928. In 1927 Alex Jackson and His Plantation Orchestra had recorded several hits on Gennett Records of Richmond, Indiana, which would have certainly been familiar to the Cincinnati dancing crowd.

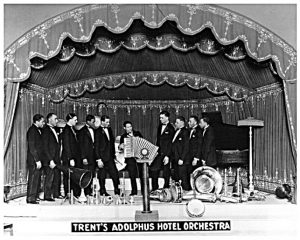

Alphonso Trent Collection, Fort Smith Museum of History

Another notable band to play the Greystone was Alphonso Trent and his 12 Black Aces, the longest-running house band at Dallas’s Adolphus Hotel (18 months!). Trent’s orchestra played the territory band circuit of the Midwest and East between 1927 and 1929.

Courtesy of the Hogan Jazz Archive Photography Collection,

Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University

Bryant’s New Orleans Syncopators, with leader Wallace Bryant originally from Paducah, Kentucky, were hired from New Orleans to play the annual Greystone Halloween masquerade party, October 31, 1929.

Greystone Manager, Scheffer, perpetually scouting new talent, attended the annual “Battle of the Bands” in 1929 at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom, one of the few ballrooms in the U.S.A. with a no-discrimination policy.

Savoy Ballroom, New York Public Library,

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

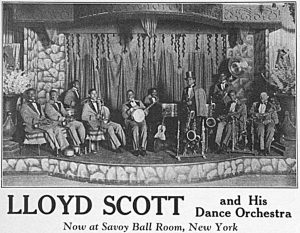

For the Greystone’s glamorous first birthday celebration he booked the winners, Lloyd Scott and his Symphonic Syncopators, with brothers Lloyd on drums and Cecil on clarinet or sax alternating as band leaders, both from Springfield, Ohio.

The Black house band at Detroit’s Graystone, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, another band that began in Springfield, made the first of several appearances at the Music Hall ballroom later that year. Breaking attendance records on New Year’s Eve in 1929 was Jordan Embry, born in Richmond, Kentucky, and his Bluebird Entertainers with headliner Lillian Thornton, a member of the legendary all-Black Broadway musical, Shuffle Along.

After Shuffle Along closed on Broadway, the cast spread out across the country to start solo careers. Noble Sissle, the show’s lyricist, formed his own band and traveled Europe for five years as Noble Sissle’s Ambassadeurs and played the Greystone on their return in 1931.

September 9, 1931

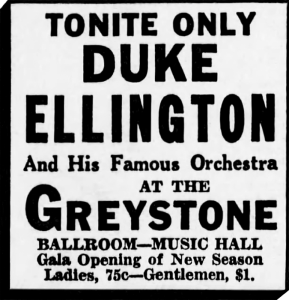

The Greystone’s 1931 gala opening featured Duke Ellington’s Orchestra with singer Ivie Anderson, the “Mistress of the Blues.” She toured with Ellington in the 1930s and was most famous for her version of “Stormy Weather,” before Lena Horne popularized it in the 1943 film.

Anderson’s first recording was with Ellington and his orchestra, the smash hit, “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).

Advertisements for Ellington’s first performance in Music Hall reveal the patronizing attitudes of the time: Ellington is referred to as the “incomparable master of jungle harmonies,” the “colored Rudy Vallée,” the “colored King of Jazz,” and that “Paul Whiteman thought so well of his (Ellington’s) music that he plays some of it himself.” The ad appears to be geared toward white audiences who may have never before heard Ellington’s Orchestra. The review stated the “capacity crowd pepped up to a high state of dancing enthusiasm to the hot rhythms of Duke Ellington and his Orchestra and attracted for the occasion not only its regular clientele but large numbers of people who are not usually seen in a public ballroom.”

1935-36 Trianon & 1936-37: Dirigible of Dance

At the height of the Great Depression in 1935, the Ballroom’s lease was transferred to the Music Hall Association with John J. Behle as manager. In its first season, it assumed the name of the Trianon, after Chicago’s famous Trianon ballroom. In its second season, it was renamed “The Dirigible of Dance” and decorated with silver material draped from the iron rafters, with portholes painted along the side walls to resemble the interior of a dirigible airship.

Cincinnati Enquirer, September 13, 1937

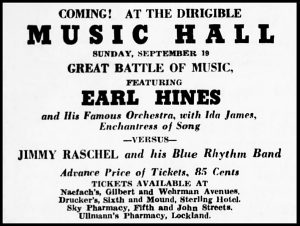

The 1936-37 season sported its own “Battle of the Bands” featuring Earl “Fatha” Hines and His Famous Orchestra, with Ida James the “Enchantress of Song,” versus Jimmy Raschel and his Blue Rhythm Band. Hines was known as a hot style jazz pianist, and he and his 20 musicians were the house band at Chicago’s Grand Terrace Café.

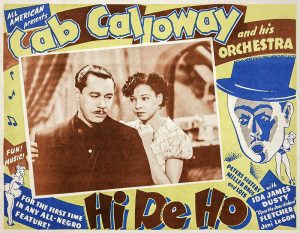

Just 16 years old, Ida James known for her “baby talk” voice had won Amateur Night at the Apollo and signed with Hines immediately after. She went on to work with Erskine Hawkins, a solo career, and movie-star roles with Nat King Cole and Cab Calloway.

Ida James plays Cab Calloway’s manager

Danville, Illinois, native, Jimmy Raschel and his ensemble was a top territory band in the Midwest circuit. Several members of his band went on to become early pioneers of the Bebop jazz style, including Sonny Stitt (alto sax) and Howard McGhee (trumpet).

The Union, December 26, 1935

The Greystone’s “Battle of the Bands” might have been one of the first exclusively for a Black audience because tickets were sold at the Sterling Hotel and Sky Pharmacy, Black businesses in Cincinnati’s West End. Although the newspaper does not tell us who won the battle that night, the “The Dirigible of Dance” lasted for only one season, as the glamour of dirigibles went down in flames when the Hindenburg crashed on May 6, 1937.

The Union, March 15, 1934

Although most dances in the Greystone seem to have been for white audiences, clues that some nights were reserved for Black dancers begin to appear in the newspapers. In July 1937 an invitation for an integrated audience appeared with an announcement of Cab Calloway and his Cotton Club Band coming to the Greystone: “Dancing will be chiefly for members of Calloway’s own race, but while [sic] enthusiasts for his music will be welcome.”

Between engagements of Black performers playing early jazz in the Greystone were white orchestras playing “collegiate” music of the Roaring ’20s into big band music of the ’30s, some with well-known territorial leaders such as Ace Brigode, Beasley Smith, Whitey Kaufman, Michael Hauer, James Dimmick, and Guy Lombardo.

On October 2, 1937, the Music Hall ballroom changed names under new management of the Topper Amusement Company, as the Topper Ballroom, but the name Greystone would continue to show up in advertisements until 1958, often as an unspoken signal that the event was for Black patrons.

Jazz, America’s classical music, came to life in Music Hall’s South Hall ballroom, which would regularly debut the most notable Black musicians during the first decades of the 20th century. The energetic syncopated rhythms and complex improvisational music performed by the leading talent of the day entertained Cincinnatians from all walks of life. The Greystone was a major stop for musicians on the Midwest territorial circuit as well as the hottest bands from the metropolises of New York City, Chicago, and Detroit. As the big band era blossomed into the 1940s, Music Hall continued to be the city’s premiere venue for music and dancing, and the Greystone helped define Cincinnati as one of our nation’s most notable music cities.