by Thea Tjepkema

The phenomenal singing careers of four women in the nineteenth century were announced and recognized in advertising with the title ”PATTI.” Three were sisters born with the last name, but when the career of the extraordinary African American operatic singer Sissieretta Jones skyrocketed at the turn-of-the-century, she was better known as the ”Black Patti” than her given name. Each performed in Cincinnati on concert tours. Three appeared in Music Hall in its early years, as one of the largest and most prestigious halls in America. In Cincinnati, as around the world, these sensational singers were received by huge crowds of fans who were thrilled by their artistry.

As daughters of Italian operatic tenor Salvatore Patti and Spanish soprano Caterina Chiesa Barilli-Patti, the Patti sisters were destined to be great singers. All three were born in Europe: Amalia (b. Paris, 1831), Carlotta (b. Florence, 1835), and Adelina (b. Madrid, 1843). They further developed their singing in New York City when their family moved there in 1847.

Amalia Patti

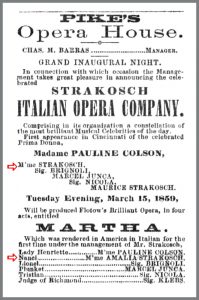

The oldest daughter, Amalia, a soprano, performed in operatic productions and in concert programs there and across the country with her husband, pianist, composer and impresario Maurice Strakosch. His Italian opera troupe visited Cincinnati twice in the 1850s performing at Smith and Nixon’s Hall and Pike’s Opera House. Though never the prima donna in these productions, Amalia was beloved by Cincinnati audiences. Her performances paved the way for future visits by her sisters.

Carlotta Patti

Vänersborgs Museum Sweden

The second sister, Carlotta had star quality and possessed an exquisite voice earning her the nickname the ”Queen of Song.” Despite her talent, she shied from dramatic roles on the operatic stage because of an irregular gait caused by a shorter leg at birth. Nevertheless, she secured her career on the concert stage with her vocal gifts as a coloratura. Carlotta was famous for her high G# and toured North America and Europe for fifteen years.

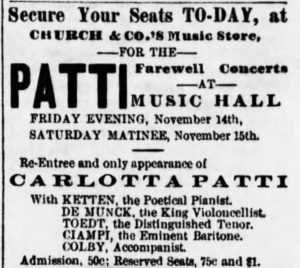

At the height of Carlotta’s fame, she appeared numerous times in Cincinnati between 1862 and 1879 with celebrated piano virtuosos Louis Moreau Gottschalk and Théodore Ritter, in Pike’s Opera House and Smith and Ditson’s Hall. She made her debut in the newly completed Music Hall on her farewell tour of 1879. Two thousand attended her concert in the main auditorium.

The program included Karl Eckert’s display piece Echo Song, made famous by Jenny Lind, ”The Swedish Nightingale.” Carlotta received rave reviews for her voice which was touted as fresh and full of youthful vigor; The Cincinnati Enquirer called her the ”Queen of the Concert-room” and stated her clear sweet ring made her the finest concert singer of the age.

Despite Carlotta’s incredible talent, she was perpetually overshadowed by the youngest sister, Adelina. Carlotta once canceled an engagement because a newspaper advertisement for a concert included the line ”Sister to Adelina.” In a letter to the editor in response, Carlotta wrote,

Though but a twinkling star by the side of the brilliant planet (Adelina) … I am too proud of the humble reputation Europe and America have confirmed to allow any-one to try to eclipse my name…by approximation…(with) my dear sister, to whom I am bound by the tenderest affection.

As Carlotta’s star was descending, her sister Adelina’s continued to rise.

Adelina Patti

Adelina Patti is considered to be one of the most illustrious sopranos of the nineteenth century. A child prodigy, she became a celebrity on multi-year tours in the United States between 1851-57, with her brother-in-law, Maurice Strakosch as her manager. At the age of 14 she toured the West Indies with Louis Moreau Gottschalk as accompanist. On their final concert in San Juan, Puerto Rico, she performed on the piano as well. Adelina made her operatic debut in Lucia di Lammermoor at the age of 16 at the New York Academy of Music; at 18 she debuted at London’s Covent Garden, where she reigned for 25 years. She went on to sing leading roles in all the major opera houses throughout Europe.

1882 CMC Opera Festival Program, from the Collection of The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

Adelina first sang in Cincinnati Music Hall in Handel’s Messiah at the 1881 May Festival. She was paid the incredible sum of $4,500, equivalent to $110,000 today. The Enquirer quipped that she was paid more than a dollar for each of the 4,000 words she sang. She returned in 1882 for the second Opera Festival of the College of Music of Cincinnati (CMC) to sing a series of concerts of arias and operatic excerpts over five days. In anticipation of her arrival, 50,000 lithographs of her photo were printed in a souvenir program and sold at the Alms and Doepke department store.

Calamity befell the festival when, upon her arrival, Adelina was diagnosed with laryngitis. Unable to perform, her appearance was postponed day after day, with local singers taking her place to the consternation of ticket holders. On the fifth day of the festival, February 18, 1882, Adelina had recovered sufficiently to sing to an audience of 7,000, filling every inch of standing room in the main hall and corridors. An additional performance was added to the Festival on February 20, and although the musical highlight was an aria from Verdi’s Aïda, Adelina’s costume stole the show: a Nile green satin dress with red roses embroidered across the chest, skirt, and train, with cherry-sized diamonds on a belt encircling her waist.

If the presence of such an international operatic sensation was not enough, Oscar Wilde was also in Cincinnati. He visited Rookwood Pottery with Maria Longworth Nichols and lectured on decorative art. He was the ”cynosure” of attention in the director’s box at Music Hall for Adelina’s performance, often standing during the concert in rapt attention.

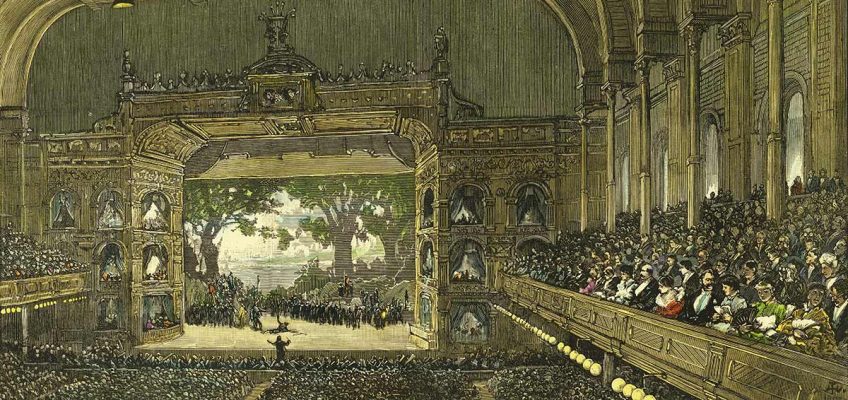

In 1883, Adelina returned for the third CMC Opera Festival where she sang leading roles in full productions of La Traviata, Semiramide, Don Giovanni, and Donizetti’s Linda di Chamouni with London’s famed Mapleson Opera Company, with soloists, a core of 40 musicians, and 50 choristers. Two hundred voices from the CMC chorus and Germania Maennerchor, as well as 60 regional orchestral players, supplemented the forces. A temporary proscenium arch was constructed on Music Hall’s stage, with incorporated box seats. The arch was decorated by Cincinnati artist John Rettig, who also created the elaborate sets and scenery.

Sell-out crowds dressed in their finest clothing were bedazzled by Adelina’s diamonds, as big as chestnuts and plums. The Enquirer described her singing as perfection with brilliant vocalization, pure intonation, and carefully detailed interpretations.

Adelina ended the ten-day festival with an encore of her signature piece Home Sweet Home. After a moment of enrapt silence, the audience burst into thunderous applause, waving handkerchiefs, libretti and programs. Three years later, Adelina made her final appearance at Cincinnati Music Hall: a one-time concert performance of the second act of Flotow’s Martha, on March 19, 1887. Critics were harsh about her damaged voice and second-rate orchestra accompaniment; an article in the American Israelite declared the show to be a money-making scheme by lessees bamboozling concertgoers for seats costing $3. Eight years later Adelina retired from regular engagements and settled in her palatial estate in Wales.

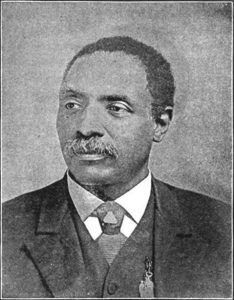

Sissieretta Jones

Metropolitan Printing Co., Library of Congress

Sissieretta Jones was one of the most influential African American artists of the nineteenth century. She was given the moniker ”Black Patti” after Adelina Patti. However, she personally preferred the title ”Madame Jones.” The daughter of a formerly enslaved father who was a carpenter and pastor, and mother who was a washerwoman, Sissieretta was born in Portsmouth, Virginia in 1868, and began singing at the age of six in her father’s Baptist Church in Providence, Rhode Island.

Sissieretta began formal music training at 15 at the Providence Academy of Music and at the age of 18 continued at the Boston Conservatory. In 1888 she drew a crowd of 8,000 at her debut at the Philadelphia Academy of Music. That same year made her debut at Steinway Hall in New York City. While there, Sissieretta was encouraged by Adelina Patti’s management to tour the West Indies, where she performed between 1888-89. On tour she performed spirituals and folk music with an ensemble of nine African American singers, the Tennessee Jubilee Singers. A second tour included a new ensemble for virtuosic classical and operatic repertoire as well as popular songs. For the next six years, Sissieretta performed across North America and Europe on stages where musicians of color were welcomed, to audiences of all races.

Sissieretta had a stellar season in 1892-93. During that period she appeared in several performances to a combined, incredible crowd of over 75,000 in the Grand Negro Jubilee in Madison Square Gardens. On February 13, 1893, she was a soloist in an ensemble of the first African Americans to sing in the main auditorium in Carnegie Hall in a fundraising concert for Will Marion Cook’s production of Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Madame Jones on Music Hall’s Stage

The following month, during the weekend of March 10-12, Sissieretta Jones made her Cincinnati debut in Music Hall. For her Friday matinee, 2,500 people, composed of the ”best element of white and colored citizens,” attended the concert. She was accompanied by an all-white cast: the Arion Lady Quartet of Chicago and celebrated mandolin virtuoso H.W. Wadhams of New York City. She sang various operatic works, including arias from Bellini’s Norma and Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine and won multiple ovations. Madame Jones sang her popular Comin’ thro’ the Rye as an encore. Sissieretta was described as having a ”pleasing face aglow with feeling while singing the most difficult staccato passages with perfect composure and ease, indicating thorough knowledge of her art.”

G.F. Richings Evidences of Progress Among Colored People, 1903, pg. 333.

Six years after Adelina Patti’s final performance here, local music critics declared Jones’ outstanding performance as the best given in Cincinnati in some time.

Finding public lodging as a Black performer was a challenge, in Cincinnati Sissieretta stayed at the Kenyon Avenue home of African American Chiropodist, Dr. Jared Carey. Later that summer, on June 22, she returned to perform with Mapleson’s Opera Company at Music Hall. The concert was pronounced a success in the Enquirer’s Items on the Wing column on African American news. However, the troupe departed for their next performance in Louisville with many bills left unpaid. A Cincinnati firm that was owed for advertising confronted her manager and took him to court.

In Louisville, Sissieretta’s concert was successful and attended by the finest of Black society; she and her accompanist were the first African Americans to stay at the Gault House. Mme. Jones was interviewed by a Courier-Journal reporter who asked about the prospects for vocalists of color in the operatic field. She replied,

The color of our skin is still a great drawback to us, but in time I believe, it will pass away. The position of any colored girl would be elevated by becoming a professional singer if she has qualifications, and I believe that the time will come when they will be numerous.

As for financial success, she replied,

Several years ago I made a tour of South America and the West Indies and was met with great financial success…trouble is that the managers take advantage of us sometimes and get nearly all the money.

Over her career, Jones performed for U.S. presidents at the White House and across Europe before royalty. A newspaper in Wales in 1893 reported Adelina Patti had given Madame Jones a diamond brooch as a testament to her appreciation for her talent. She received medals and jewelry from dignitaries and fans around the world which she proudly wore for concerts, but she was never able to fully realize an operatic career, especially in America. From 1896-1915 she toured with a vocal ensemble called the ”Black Patti Troubadours,” which changed its name in 1909 to “The Black Patti Musical Comedy Company,” a vaudeville group she starred in, performing operatic songs, spirituals and popular ballads.

Mme. Jones retired to her home in Providence in 1916. Although she was the highest paid African American artist of her time, she only made a fraction of what her white peers earned. In her final years, she was forced to sell her jewelry and medals for the necessities of life. She died penniless in 1933 and was buried in an unmarked grave, which finally was adorned with a headstone in 2018.

Author Thea Tjepkema is a historian and preservationist. She is also a member of the Friends of Music Hall Board of Directors.

Featured Image: CMC Opera Festival, Scene from the first act of Lohengrin, by H.F. Farny, Harper’s Weekly, February 3, 1883.

Lee, Maureen D. Sissieretta Jones: ”The Greatest Singer of Her Race” 1868-1933. The University of South Carolina Press, 2012.