Theodore Thomas, the famed conductor, is known for bringing symphonic music and orchestras to people who had never heard this type of performance. In order to draw individuals from all walks of life, Thomas mixed both light and serious (popular and classical) pieces and is credited with introducing Richard Wagner's music to America.

Thomas was born in Germany in 1835 and taught himself how to play the violin. By age 14, he was touring the United States as a soloist.

Following his debut as a conductor—here, too, he was self-taught—Thomas formed his own orchestra which toured the U.S. for twenty years.

The Making of the May Festival

In 1872, when Thomas brought his orchestra to Cincinnati on his regular tour, Maria Longworth Nichols and her husband George Ward Nichols got together with Thomas to discuss an idea they'd had of presenting a festival of choral music.

This festival would be quite different than those held in the Saengerfest and German Singing Society traditions, which included a lot of socializing, food and beer drinking. Thomas was eager to fashion performances and he signed on as music director of the then-biennial May Festival, a position he held until 1904.

Much to Thomas's credit, the first May Festival was quite a success.

Thomas in Cincinnati

The Nichols, along with Reuben Springer, wanted to keep their talented music director in Cincinnati as much as possible.

They built the professional-level College of Music in 1878 and hired Thomas as Director. George Ward Nichols became the College's President.

This mirrored their interests: Mr. Thomas's was in artistic development and Mr. Nichols's concern was for the bottom line.

It wasn't long until Thomas and Nichols started "butting heads," each wanting to be the one to determine policy for the institution.

In early 1880, it was reported that Mr. Thomas wanted reforms to make the institution a "real college of music" with him as the "real and undisputed head." He wanted the college to be more like the great musical conservatories abroad which offered fixed terms of study over several years.

The Directors of the College of Music agreed only to a few minor changes. Their lack of support for his reform angered the disciplined Mr. Thomas, who was known to have a temper.

Thomas Resigns

Mr. Thomas’s resignation letter was described by Reuben Springer as “not gentlemanly or polite.” Mr. Springer added that Col. Nichols had made the College self-supporting and should that end, the College would cease to exist.

Despite being only eighteen months into his five-year contract, Thomas left the college and the city.

However, Thomas maintained his position with the May Festival and was reported to have been on good terms with many in the community.

Strictly a Local Matter

While it seems to be strictly a local matter, Mr. Thomas’s reputation - and that of the May Festival - extended across the country and newspapers in various cities seized upon the news.

- The Boston Globe opined that Mr. Thomas, a first-class conductor and music director, finally realized the mistake he made in agreeing to work in a provincial town such as Cincinnati.

- The Brooklyn Eagle took the opposite tact, stating that while Mr. Thomas “is an orchestral conductor of undoubted merit, his opinion of his own merit is considerably larger than is warranted by the facts.”

Following his resignation, Thomas returned to New York where he was once again welcomed as the music director of the Philharmonic.

Thomas later became the first music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The city built a new hall for the orchestra in 1904 and Thomas conducted the dedicatory concert there on December 14th. He had, however, contracted the flu during the rehearsals for that concert and died of pneumonia on January 4, 1905.

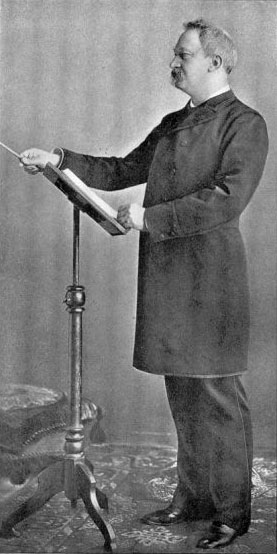

Theodore Thomas