By Thea Tjepkema

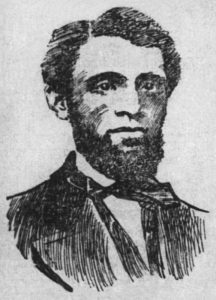

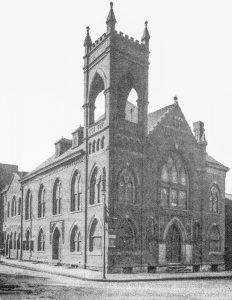

On January 4, 1898 the funeral of Fountain Lewis, Cincinnati’s most esteemed African American barber for more than fifty years, drew a large crowd that overflowed onto Mound and Richmond streets at Union Baptist Church. The Enquirer reported “distinguished white people” and hundreds of the “higher circles of the deceased’s race” were in attendance.

The official Board of Deacons of the church, some half-a-century associates of Lewis, and prominent gray-haired white citizens sat up front, which the Enquirer described as a “striking picture of homage paid by two races.” Reverend Dr. Prowd spoke about Fountain Lewis’s character as “faithful to himself, his family, his friends, his race, his country and true to the American flag; he had principle and stood up for it under all circumstances, being a man strong in his convictions and fearless in action. He placed before the community a life of flawless honor and integrity.”

Reuben Springer’s Donation

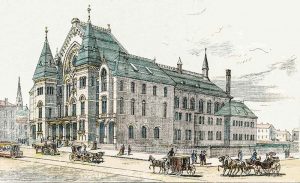

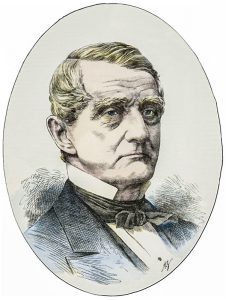

Twenty years before, Cincinnati Music Hall had its grand opening on May 14, 1878, with more than 6,000 people squeezing into a 4,428-seat auditorium. 10,000 more stood outside trying to listen to the music coming from the windows. The third May Festival opened with selections from Gluck’s opera Alceste by the orchestra, chorus, and soloists. Then the dedication ceremonies began with Reuben R. Springer walking on stage to wild enthusiasm and deafening cheers reportedly lasting 15 minutes. He was accompanied by prominent men who helped solicit the funds and organize the construction of the hall.

May 15, 1878

Reuben Springer had given the generous lead donation of $125,000 two years prior to kick off the subscriptions campaign with the stipulation that an equal sum would be raised from local citizens. Springer was extremely humble and wished that the building would not carry his name but be titled “Cincinnati Music Hall” to honor all who contributed. He gave thousands more when construction continued for the north and south wings, which opened in 1879 for the annual Grand Industrial Expositions.

Springer was showered with bouquets of flowers tossed from the crowd. Then Julius Dexter spoke about Springer’s initial offer, which encouraged the community to chip in:

“…generous as he has been, it is not the amount of his gift which especially entitles him to our gratitude. Other persons may have given as much; possibly, in proportion to their means more. Who may say that the contribution of the colored barber, or of the hard-working mechanic of a rolling-mill, is not the equal in liberality with any thousand dollars, or even with the largest sum given? The liberality of Mr. Springer consists chiefly in its usefulness, its modesty, the wisdom of its conditions, and particularly in its invitation of aid from others. … It is the privilege of wealth to foster, protect and assist good works, and praise is rightly his who calls to himself as co-equal associates in a worthy enterprise, men of every class and of various means. This praise, as well as gratitude, we give tonight.

Citizen Subscribers to the Fund

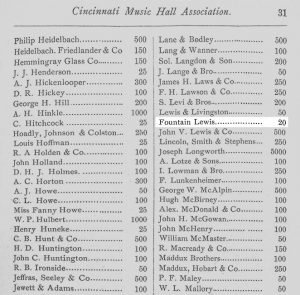

The Cincinnati Music Hall Association’s 1877 annual report listed prominent men — Joseph Longworth, President; John Shillito, Treasurer; and Julius Dexter, as Secretary and Chairman of the Building Committee — who were among the 386 subscribers donating a total of $253,331.

Donors listed were both businesses and individuals, primarily men and six women, who gave mostly in denominations of 1,000, 500, 250, 100, 50, or 25 dollars. Large philanthropic gifts came from businesses: Cincinnati Gas, Light & Coke Company, Cincinnati Consolidated Street Railroad Company, Christian Moerlein Brewery, and Procter & Gamble, as well as wealthy citizens: Larz Anderson, William H. Harrison, John L. Stettinius, Charles W. West, and Mrs. Sarah B. Carlisle. Twenty-two people gave $25, and one person donated $20: Fountain Lewis, Cincinnati’s most prominent barber.

Lewis in the Community

Lewis was an altruistic man who donated to many charities; especially for the “elevation of his own people,” stated the famous African American newspaper publisher and author Wendell P. Dabney in his Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens, printed in 1926.

Dedicated to the Union Baptist Church for 55 years, Lewis was a trustee on the board and had given generously to the construction of its church at Mound Street. He was also a trustee of the Crawford Home for Aged Colored Men in College Hill. Fountain Lewis was certainly the “colored barber” mentioned in Julius Dexter’s speech. Lewis’s $20 donation would compare to a nearly $500 gift today, a generous donation even for an affluent African American in the era.

Early Life

Fountain Lewis was born on a plantation in Frankfort, Kentucky, in August 1820. His mother was enslaved while pregnant, but was free before his birth, according to Lewis. In an interview in the Enquirer, he recalled his mother worked for “dimes a day” to buy her other children out of slavery. They came to Cincinnati “a month within the time that General Harrison died” in April 1841. Lewis found work as a barber to help buy freedom for his father, who lived to be 108; his mother was over 80 when she passed.

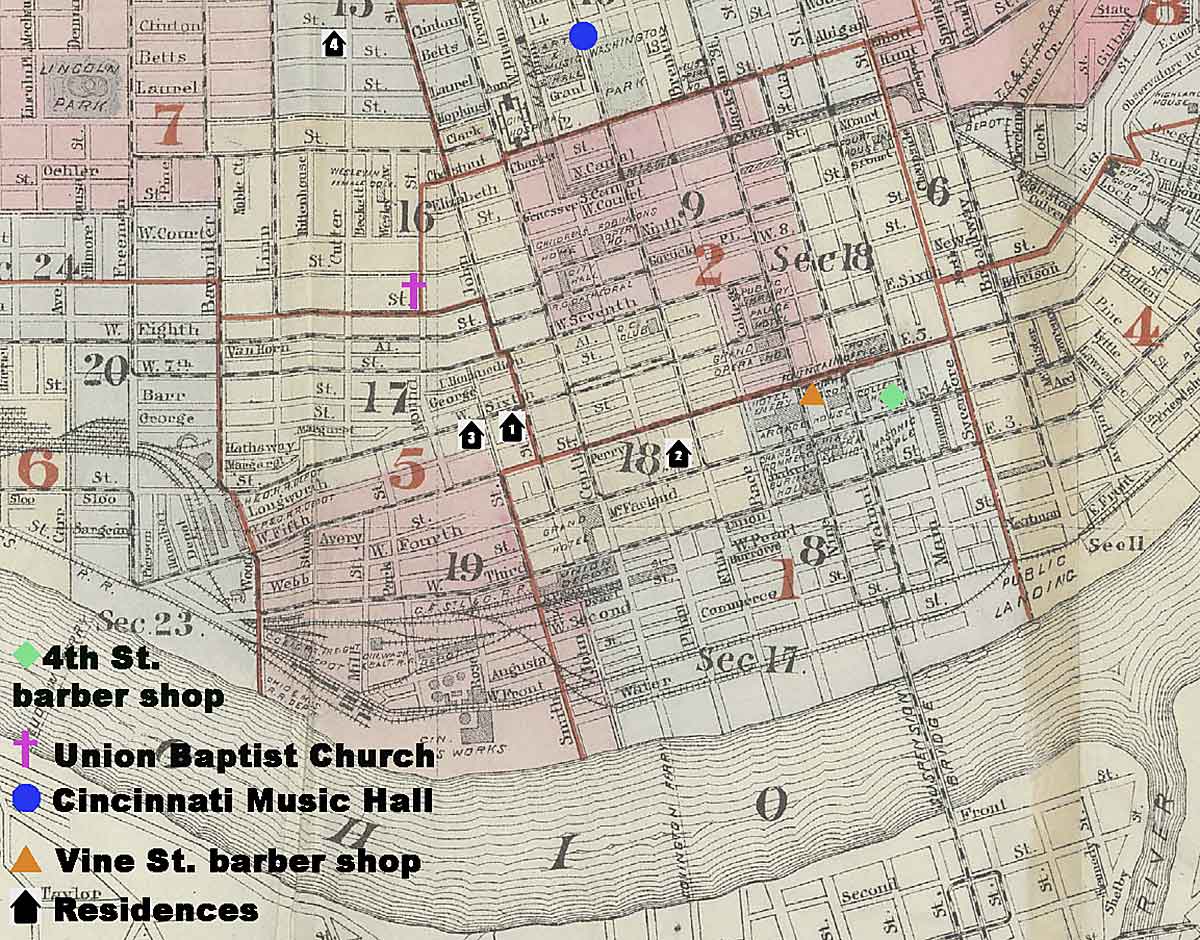

Lewis’s Barber Shops & Residences

According to Dabney’s biographical sketch, in Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens, Lewis began working in the early 1840s in a barber shop kept by “Ferree, a Frenchman.” Lewis was overlooked in the 1842 Williams’ Cincinnati Directory, where 60 African American barbers were listed. (Undoubtedly many more, were unlisted.)

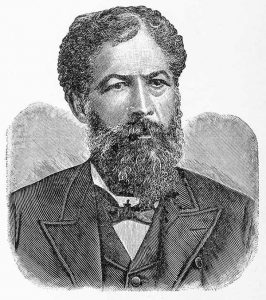

Credit – North Wind Picture Archives

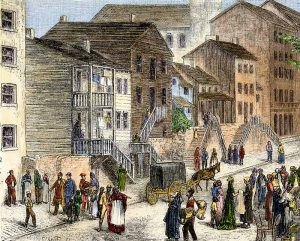

Cincinnati grew rapidly starting in 1840: The Sixth U.S. Census counted 44,098 whites and 2,240 Blacks. The city was becoming densely populated, and African Americans lived in every ward of the city. Although the rise in population benefited Black barbers, whites and Blacks competing for similar jobs caused tensions to escalate. Lewis arrived just months before the 1841 race riots, which began with an angry white mob attacking Blacks in “Bucktown,” an east-side downtown neighborhood.

After this violent destruction of property and the reinforcement of “Black Laws,” it took years for economic recovery for many African Americans in Cincinnati. Still, one of the best wage-earning jobs for an African American man for most of the nineteenth century remained what was termed a “tonsor” or “tonsorial artist” (from the Latin tondēre, meaning to shear, clip, or crop). Black barbers thrived, primarily because they cut the hair of white men, which enabled some to earn enough money to own their own shops, homes, or property.

A Prominent Citizen

Lewis was not listed in city directories until 1851, but his existence as a barber and community leader of high moral character was recognized by his signature on a petition to City Council in 1843. Along with 54 local barbers, he lobbied for a law to close barber shops on Sundays with the belief that “the Sabath should be a day of rest.” Barber shops breaking the law would be fined, as were other businesses closed on Sundays.

Lewis first appeared in the 1851-52 Williams’ Directory, along with John P. Ferrie (likely the “Ferree” Dabney mentions) at the same address. Both were listed as barbers in a shop on the north side of Fourth Street between Main and Walnut. In the 1857 directory Ferrie and Lewis are listed as barbers at 4 W. Fourth Street. Lewis’s wife Daphney is listed as a dressmaker on Longworth Street (map: home 1), also their home address, in downtown’s west side. Ferrie moved to New York City in 1857 and gave the shop to Lewis. In the 1858 directory Lewis is listed with a new partner, George Tosspot. They worked together until 1868 when Lewis became the sole proprietor.

Lewis lived at three addresses between 1866 and 1892, moving from Home Street (map: home 2) in the central part of downtown, to Smith Street (map: home 3) on the west side, before settling just three blocks west behind Music Hall, for 18 years, at 92 Betts Street (map: home 4), with Daphney and their son, Fountain C. Lewis Jr. (Fountain Jr. is listed in 1880, as a barber managing his father’s shop at 182 Vine St.) In an interview in the Enquirer, just eight months before his death, Lewis said his barber shop was on the northwest corner of Fourth and Main for 44 years; he was forced to move by city development in 1884 to 34 W. Fourth Street.

Ten years later he moved his residence to May Street in Walnut Hills. (His son continued to live on Betts Street.) By 1895, three years before his death, Lewis was listed as a barber at 510 Race Street; his son continued to work on Vine Street. The revered barber, Fountain Lewis Sr. cut hair in Cincinnati for at least 54 years before passing away peacefully in his home at 2409 May St. in Walnut Hills. He walked back and forth every day from his residence to work, even at the age 77, the year he died.

Magnificent Men

An Enquirer reporter interviewed Fountain Lewis while he was ill in bed on December 28, 1897. The reporter described a well-furnished home with a portrait of Lewis’s mother, born in the eighteenth century, hanging in the parlor. Fountain said,

No, I was never a slave … I had most as hard a time, however, in my younger days as though I had been a slave. But no harder than lots of my companions who, like me, were born in Kentucky about that time.

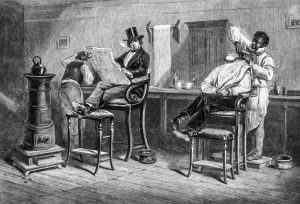

Early in his career, Lewis stated there was no Chamber of Commerce, but white men would conduct business in his shop while getting shaved clean and their long hair trimmed and soaked in thick hair oil, fashionably curled in a roll around the back of their necks and over their ears.

For many years, Lewis’s shop was on the same block as the City Council’s chambers, enabling him to remain abreast of local politics while snipping hair. His Fourth Street shop was not far from his landlord, Jacob L. Wayne, who owned a hardware and cutlery store on Main, between Race and Elm according to the 1851-52 directory. “At first, I paid him [J.L. Wayne] $29.15 a month and then $50 a month a long time after that.” Lewis was proud to operate his own business in the “high rent” heart of the city.

Grand and magnificent men were customers of mine at that same old shop. There was Reuben R. Springer — and he got me to be one of the subscribers in the fund to build the Music Hall, and you can depend on it I’m mighty proud of the fact now. And there was Charles Telford, who was a gem of a gentleman! Ah, I wish Cincinnati had more Springers and Telfords today!

Lewis listed other famous customers: Rufus King; Josiah Lawrence; (John) Scott Harrison, son of President William Henry Harrison; Kentucky Governor Charles S. Morehead; Nicholas Longworth; General William Haines Lytle; U.S. Senator Henry Clay; Tom Corwin; John J. Crittenden; James J. Faran; and Dick (Richard Mentor) Johnson. He reflected, “Nearly all my old customers are out in Spring Grove now.”

Fountain Lewis Sr.’s Family

With his wife Daphney R. Cotton, Lewis had 11 children, but only two were living at the time of his death: Fountain C. Lewis, Jr., and Newman Lewis. Both followed in the footsteps of their father as barbers. Fountain Jr.’s shop at 432 Vine and Newman’s at 524 Mound were in the 1898 Williams’ Directory. In 1897, Fountain Jr. moved from the family home on Betts Street to 1017 Foraker Avenue around the time he married Mary Louise Ferguson. Daphney died at home in 1891, her obituary in the Cincinnati Commercial Daily Gazette noted that Lewis’s father died earlier that year. The following year Lewis married, Lucetta Tanner West, the widow of William West, a prominent coal dealer and partner in West & Clark Company. She was the granddaughter of Charles McMicken, founder of the University of Cincinnati.

Fountain Lewis Jr.’s Family

Fountain Lewis Jr. had two children: Frederick William, and Mary Maxberry. Fountain, Jr., eventually left barbering and went into undertaking with his son, according to Dabney’s Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens. Fred eventually moved his business to Cleveland; his daughter Louis Lewis Noel remained in Cincinnati with her husband Roy Wilkins Noel. Fountain Lewis Jr. continued in his father’s philanthropic ways, taking his place on the board of trustees for the Crawford Aged Men’s Home and serving on the first board of the Home for Colored Girls, established in 1914. The home was at 649 West 7th Street as a place for African American women to stay who were new to the city and needed help finding employment. Trustees included prominent citizens: J.G. Schmidlapp, James N. Gamble, Mary Emery, and Wendell P. Dabney.

The Legacy of Cincinnati’s Tonsorial Artists

In July of 1850, Frederick Douglass visited Cincinnati for eight days and met William W. Watson, another of Cincinnati’s African American barbers. In the North Star, Douglass wrote that among this most “industrious, enterprising and public-spirited colored community” he had encountered, Mr. Watson enjoyed utmost “respect and esteem among his fellow-citizens.” Watson, a contemporary of Lewis, ran a successful shop in the heart of the business district, and was typical of the legion of African American barbers in Cincinnati, promulgating the craft and supporting the next generation of tonsorial artists. Born into slavery, Watson’s freedom was purchased by his brother-in-law, a successful barber in Cincinnati, and set him up in the business. Watson, in-turn, was perpetually helping others including serving within the Underground Railroad network. Watson was also very generous in the community, including making the single largest donation to purchase the Union Baptist Church building on Baker Street. Along with Fountain Lewis, he was a co-signer of the 1843 petition to close barber shops on Sundays.

In 1840 John Mercer Langston, at the age of 10, came to Cincinnati to be near his brother Gideon whose barbershop was also along Fourth near Main. John boarded with the Watson family and 17 others and described Watson’s home as “well-furnished with pleasant rooms and parlors.” Langston described Cincinnati’s African Americans whom he met through Watson as having, “intelligence, industry, thrift and progress; and in matters of education and moral and religious culture, furnished an example worthy of imitation.” Langston worked in Watson’s barber shop, and the Watsons became his family.

Young Langston learned his first lessons in civics, politics and leadership from Watson, at school and church in the African American community. He also listened to the predominantly white customers talking freely in the barber shop. Langston went on to attend Oberlin College, was Ohio’s first African American attorney, a founder of the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the Civil War, the first dean of Howard University Law School, and Virginia’s first African American Congressman.

Barbers’ Day at the 1888 Centennial Exposition

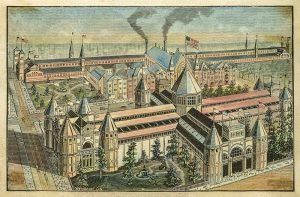

October 15, 1888 was “Barbers’ Day” during the last annual Grand Industrial Exposition held in Cincinnati Music Hall. The “Centennial Exposition of the Ohio Valley and Central States” celebrated the 100th anniversary of the first settlement of the Northwest Territories. It opened with fireworks on July 4 and closed four months later on November 8, a little over 100 days for the 100th Anniversary.

By the late 1880s the public’s interest in Grand Industrial Expositions had waned. For this 14th (and final) exposition in Cincinnati Music Hall, “themed days” were designed to attract as many attendees as possible. Exposition commissioners knew Cincinnati had more than 350 barber shops listed in the city directory, and each of these barbers had numerous devoted customers. “Barbers’ Day” would draw a crowd. In the Enquirer’s African-American news column “Items on the Wing” it was stated, “the barbers will turn out in large numbers … as the colored barbers are largely in excess of the white ones in this city in point of numbers, the race will, no doubt, be well represented.”

Also known as Knights of the Razor, hundreds turned out from Cincinnati, Newport, Covington, and nearby towns. Barbers who rarely had a day off closed their shops at noon and took a holiday to march in a grand barbers’ parade on a route around downtown. At 1:30 p.m. they gathered at the starting point of the parade at Thirteenth and Walnut, in front of Workmen’s Hall, “all in their finest dress, wearing dark suits and shiny plug hats and white badges inscribed with ‘Barbers’ Day. October 15, 1888. Cincinnati Centennial Exposition’.” Beards were forbidden in the procession, so all the barbers were clean shaven. Four divisions of barbers were each led by a band with the Grand Marshal Charlie Reed on horseback. Nicholas Alexander, a leader of the African American barbers, and Fountain Lewis, “the venerable colored barber, who has shaved more prominent men than any one in Cincinnati,” both rode in a lead carriage.

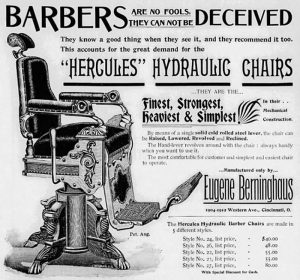

They entered the exposition entrance at Race and Thirteenth streets, Park Hall, a temporary, wooden, cruciform-shaped building in Washington Park constructed to display items on loan from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C. The barbers marched through the buildings and were welcomed with cheers and greeted heartily as guests by the Commissioner of the Day, May Fechheimer. The Enquirer reported, they “scattered and amused themselves in various ways, many visited the beer hall, one of the most enjoyable places in the Centennial with a splendid reputation.” The Foss-Schneider Company’s beer hall was in Machinery Hall, another temporary wood structure built over the Miami and Erie Canal. Sixteen hundred tickets were sold to the barbers for a raffle to win a barber’s chair donated by E. Berninghaus; and the newspaper declared the winner as H. Mueye of Henry Daum’s shop at 269 Central Avenue. The Eugene Berninghaus Company of Cincinnati (1875-1938) was the first manufacturer of barber chairs in the U.S.

Fountain Lewis knew better than most the value of Cincinnati Music Hall to inspire ALL people, for the betterment of the community. He supported its construction with a modest investment that, in retrospect, helped mold the ethos of our community. His strong moral compass and work ethic forged a successful career as a businessman and philanthropist. Despite the inherent challenges of racism in Cincinnati, Lewis made a real difference in the lives of those he touched. We now know some of his story, and how he helped fulfill Reuben Springer’s promise of a temple of music and art that would be accessible to all.

Thea Tjepkema is a member of the Friends of Music Hall Board of Directors as historic preservationist, content curator, and archivist.

Thank you for assistance and inspiration:

Stephen Headley, Reference Librarian, Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County; Anne Delano Steinert, University of Cincinnati PhD(c) Urban and Public History; Rick Pender, editor, & John Morris Russell.

References:

William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek. John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829-65. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Silas Niobeh Crowfoot. Community Development for a White City: Race Making, Improvementism, and the Cincinnati Race Riots and Anti-Abolition Riots of 1829, 1836, and 1841, Dissertation PhD, Portland State University, 2010.

Illustrations:

- Wendell P. Dabney. Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens: Historical, Sociological, and Biographical. St. Martin, OH, Commonwealth Book Co., reprint 2019; 1926 ed.

- Ernst von Hesse-Wartegg. Nord-Amerika seine Städte und Naturmunder, das Land und seine Bewohner in Schilderungen von Ernst von Hesse-Wartegg, Band II, (North America its cities and natural wonders, its country and its people, Vol. II) Leipzig, Verlag von Gustav Weigel, 1886; Stockholm, Fahlcrantz & Co. 1880. “Cincinnati: Im Negerviertel.” p. 8. Hand-colored by North Wind Picture Archives.

- E. Robinson & R.H. Pidgeon. Atlas of the City of Cincinnati, Ohio. New York, E. Robinson, 1883-4. The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County Digital Library.

- Eyre Crowe. With Thackery in America. London, Cassell and Company Limited, 1893.

- Rev. William J. Simmons, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. Cleveland: G.M. Rewell & Co. 1887. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Huston.

Established in 1864, Union Baptist Cemetery is the oldest African American cemetery in Hamilton County in its original location and is still in use by its congregation. Many formerly enslaved, abolitionists, members of the Underground Railroad, Civil War soldiers, and prominent African Americans are buried in this cemetery including:

- Fountain Lewis, Sr. (b. Frankfort, KY 8/1820-d. 1/4/1898 Cinti)

- Daphney R. Cotton Lewis (b. Mississippi 1828-d. 7/11/1891 Cinti)

- Adeline McMicken Tanner Rollins (b. St. Francisville, LA 1812-d. 1884 Cinti) mother of:

- Lucetta Tanner West Lewis (b. Pittsburgh, PA 1/1/1840-d. 9/9/1915 Cinti)

- Fountain C. Lewis, Jr. (b. Cinti 12/27/1858-d. 5/14/1929 Cinti)

- Mary Louise Ferguson Lewis (b. Cinti 12/27/1860-d. 3/3/1919 Cinti)

- Norman Lewis (d. 1903-Norman L. Lewis?)

Donations for the Union Baptist Cemetery Fund can be made online at https://www.gofundme.com/f/tuf-cemetery.