Music Hall was constructed in Over-the-Rhine in the late 1870s.

Cincinnati had been founded only 90 years earlier, but already there had been several uses for the land on which the hall sits.

Early Cincinnati

Cincinnati was founded in 1788. The city grew from there, with immigrants populating the core city area.

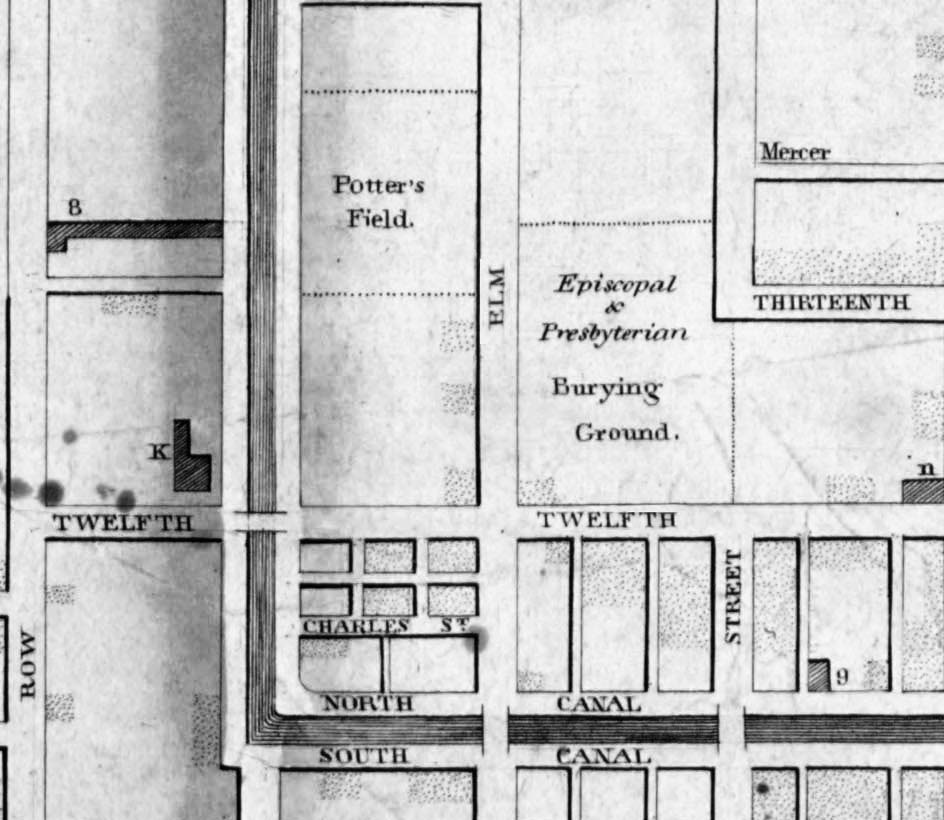

A map from 1830 points to a Potter's Field in that block. The Potter's Field was used for immigrants and paupers who had the misfortune of dying without identification, or without loved ones to claim their bodies.

By 1842, the northern part of the tract held the Cincinnati Orphan Asylum. Some twenty years later, those same individuals sold the land to the city for temporary use while a new Commercial Hospital was built directly west of that site, across the canal.

The City Grows

Once a new hospital was up and running, the North American Saengerbund Society decided the lot on Elm Street between 12th and 14th Streets was the perfect location for its 1870 convention in Cincinnati and a large wooden hall was quickly built on the site for Saengerfest.

Once the singing had ended, the hall was used for expositions, and thereafter was referred to as "Exposition Hall."

A Permanent Structure was Needed

In 1875, leading citizens started raising funds for a hall more suited to Musical Festivals, much like those presented in Europe.

Construction on Music Hall started in October, 1876, right after the Exposition Hall was torn down. It was during the excavation of the site for the new building's foundation that workers came across the first ''human remains''. Newspaper accounts at the time -- which sometimes were embellished to sell papers -- indicates that the discovery drew crowds who watched as boxes were filled with skeletal remains.

Reburial

Music Hall Association meeting minutes show that the city was not interested in helping dispose of the skeletons. W.H. Harrison was on the Association's board, as well as on the board of Spring Grove cemetery. He arranged for a plot to be used for a proper reburial of all the skeletons that were found.

Why were bones discovered during the hall's construction, but not when Saengerfest Halle was built? The previous wood-framed structure was believed to have been built without a deep foundation. Reports indicate it had a dirt floor.

In February 1927, while digging a foundation for a connecting tunnel during the remodeling of Music Hall, workers came across three coffins. A headstone for one of the coffins read: ''Sacred to the Memory of George Pollock, native of Scotland, who died October 29, 1831, age 52 years.''

According to news reports, workers stopped digging the trench when a snowstorm interfered with their work. While they were gone, souvenir hunters removed several bones, including a skull and two pelvic bones, possibly those of a young girl. Rather than move the three bodies to Spring Grove Cemetery with the skeletons found in the 1870s, they were ''given a fitting burial in the pit of the new elevator shaft,'' a four-foot cement vault.

Later that same year, as another trench was being dug -- this one under the south wing -- workmen discovered what was called a ''Valley of Death'' -- 65 graves. Again, even though watchmen were placed nearby, several skulls were stolen during the night.

Initial investigation indicated that there were traces of coffins around the bones, but all the wood had disappeared in the century between burial and discovery. Newspaper reports indicate that all were reburied where they were discovered.

Another Renovation, Another Discovery

Fast forward to early May, 1988. The history of the site and the events of 1927 were long forgotten. Workers drilling a new elevator shaft uncovered over two hundred pounds of bones. The coroner was called in to investigate the possibility of foul play.

Later a number of the bones ended up at the physical-anthropology lab at the University of Cincinnati, where they were studied in order to provide more information on the physicality of people from the early 1800s.

Forensic anthropologist and Mt. St. Joseph professor Dr. Elizabeth Murray examined the bones as part of her doctoral dissertation to see what secrets they held about life among Cincinnati's first settlers, and to compare them with bones from other Americans living in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

In the mid 1990s, Dr. Murray took students from the Mount on a field trip to Music Hall, to excavate under the Music Hall stage in hopes of finding additional bones as well as artifacts that could shed more light on early life in Cincinnati.

Digging under Music Hall for the 2016-2017 Revitalization

Looks like it happens every time they dig. During the most recent - and intensive - renovation work at Music Hall, workers checking soil for asbestos found human remains under the orchestra pit. Additional work in the north carriageway - the area between the north wing and the center building - uncovered wood coffins containing bones. The bones were respectfully removed by an archaeological firm and are believed to have been re-interred in Spring Grove cemetery with bones recovered during previous work on Music Hall.

Map of Elm Street & area - 1830

The Moselle Disaster: Where Were the Victims Buried?

In 1838, the steamer Moselle exploded just off the Cincinnati wharf, killing as many as 200 people. Initial newspaper reports indicated unidentified victims were buried in "the public cemetery" (aka, Potter's Field). To this day, it is assumed by many that they were buried in the one along Elm Street between 12th and 14th Streets. However, That wasn't the only Potter's Field in the city. Another existed directly to the west, in what later became Lincoln Park, and what is now the eastern edge of the Cincinnati Museum Center parking lot.

Reports in The Cincinnati Enquirer in August, 1876, quoted individuals claiming the final resting place of those Moselle victims included the old Presbyterian Churchyard - now Washington Park, and the old Catherine street Burying Ground. Most insisted Moselle victims were buried in the Lincoln Park Potter's Field. Only one mentioned the Potter's Field beneath what is now Music Hall.